Actuarial Report (30th) on the Canada Pension Plan

Accessibility statement

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) defines requirements for designers and developers to improve accessibility for people with disabilities. It defines three levels of conformance: Level A, Level AA, and Level AAA. This report is partially conformant with WCAG 2.0 level AA. If you require a compliant version, please contact webmaster@osfi-bsif.gc.ca.

The Honourable William F. Morneau, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Finance

House of Commons

Ottawa, Canada

K1A 0A6

Dear Minister:

In accordance with section 115 of the Canada Pension Plan, which provides that an actuarial report shall be prepared every three years for purposes of the financial state review by the Minister of Finance and the ministers of the Crown from the provinces, I am pleased to submit the Thirtieth Actuarial Report on the Canada Pension Plan, prepared as at 31 December 2018.

Yours sincerely,

Assia Billig, FCIA, FSA, PhD

Chief Actuary

Table of contents

List of tables

- Table 1 - Best-Estimate Assumptions

- Table 2 - Population of Canada less Québec

- Table 3 - Economic Assumptions

- Table 4 - Contributions - Base CPP

- Table 5 - Beneficiaries - Base CPP

- Table 6 - Beneficiaries by Sex - Base CPP

- Table 7 - Expenditures - Base CPP

- Table 8 - Expenditures - Base CPP (2019 constant dollars)

- Table 9 - Expenditures as Percentage of Contributory Earnings - Base CPP

- Table 10 - Historical Results - Base CPP

- Table 11 - Financial Projections - Base CPP, 9.9% Legislated Contribution Rate

- Table 12 - Financial Projections – Base CPP, 9.9% Legislated Contribution Rate (2019 constant dollars)

- Table 13 - Sources of Revenues and Funding of Expenditures - Base CPP, 9.9% Legislated Contribution Rate

- Table 14 - Financial Projections - Base CPP, Minimum Contribution Rate of 9.75% 2022-2033, 9.72% 2034+

- Table 15 - Progression of Minimum Contribution Rate over Time – Base CPP

- Table 16 - Contributions - Additional CPP

- Table 17 - Beneficiaries - Additional CPP

- Table 18 - Beneficiaries by Sex – Additional CPP

- Table 19 - Expenditures - Additional CPP

- Table 20 - Expenditures – Additional CPP (2019 constant dollars)

- Table 21 - Financial Projections - Additional CPP, 2.0%, 8.0% Legislated First and Second Additional Contribution Rates

- Table 22 - Financial Projections - Additional CPP, 2.0%, 8.0% Legislated First and Second Additional Contribution Rates (2019 constant dollars)

- Table 23 - Sources of Revenues - Additional CPP

- Table 24 - Financial Projections - Additional CPP, First and Second Additional Minimum Contribution Rates of 1.98% / 7.92%

- Table 25 - Progression of Additional Minimum Contribution Rates over Time

- Table 26 - Change in Assets - 31 December 2015 to 31 December 2018 - Base CPP

- Table 27 - Summary of Expenditures - 2016 to 2018 – Base CPP

- Table 28 - Reconciliation of Changes in Minimum Contribution Rate

- Table 29 - Reconciliation of Changes in Additional Minimum Contribution Rates

- Table 30 - Legislated Contribution Rates

- Table 31 - Projected Maximum Additional CPP Retirement Benefit

- Table 32 - Legislated Pension Adjustment Factors

- Table 33 - Projected Maximum Additional CPP Disability Benefit

- Table 34 - Projected Maximum Additional CPP Survivor’s Benefit, Survivor under Age 65

- Table 35 - Projected Maximum Additional CPP Survivor’s Benefit, Survivor Age 65 or Over

- Table 36 - Data Sources

- Table 37 - Cohort Fertility Rates by Age and Year of Birth

- Table 38 - Fertility Rates for Canada

- Table 39 - Annual Mortality Improvement Rates for Canada

- Table 40 - Mortality Rates for Canada

- Table 41 - Life Expectancies for Canada, without improvements after the year shown

- Table 42 - Life Expectancies for Canada, with improvements after the year shown

- Table 43 - Population of Canada by Age

- Table 44 - Population of Canada less Québec by Age

- Table 45 - Analysis of Population of Canada less Québec by Age

- Table 46 - Births, Net Migrants, and Deaths for Canada less Québec

- Table 47 - Active population (Canada, ages 15 and over)

- Table 48 - Labour Force Participation, Employment and Unemployment (Canada, ages 15 and over)

- Table 49 - Labour Force Participation Rates (Canada)

- Table 50 - Employment of Population (Canada, ages 18 to 69)

- Table 51 - Active Population (Canada less Québec, ages 15 and over)

- Table 52 - Labour Force Participation Rates (Canada less Québec)

- Table 53 - Employment of Population (Canada less Québec, ages 18 to 69)

- Table 54 - Real Wage Increase and Related Components

- Table 55 - Inflation, Real AAE and AWE Increases

- Table 56 - Average Annual Earnings (Canada less Québec, ages 18 to 69)

- Table 57 - Total Earnings (Canada less Québec, ages 18 to 69)

- Table 58 - Average Pensionable Earnings up to YMPE (Canada less Québec)

- Table 59 - Average Pensionable Earnings up to the YAMPE (Canada less Québec)

- Table 60 - Proportion of Contributors to the CPP, by Age Group

- Table 61 - Average Contributory Earnings for Pensionable Earnings up to YMPE

- Table 62 - Average Contributory Earnings for Pensionable Earnings up to YAMPE

- Table 63 - Total Adjusted Contributory Earnings for Pensionable Earnings up to YMPE

- Table 64 - Total Adjusted Contributory Earnings for Pensionable Earnings up to YAMPE

- Table 65 - Net Assets as at 31 December 2018 - Base CPP

- Table 66 - Base CPP (Core Pool) Initial Asset Mix as at 31 December 2018

- Table 67 - Real Rates of Return by Asset Type (before investment expenses)

- Table 68 - Asset Mix, Portfolio Risk and Expected Rates of Return (before investment expenses) Base CPP

- Table 69 - Asset Mix, Portfolio Risk and Expected Rates of Return (before investment expenses) Additional CPP

- Table 70 - Overall Rate of Return on base and additional CPP Assets

- Table 71 - Annual Rates of Return on CPP Assets

- Table 72 - Benefits Payable as at 31 December 2018 – Base CPP

- Table 73 - Benefit Eligibility Rates by Type of Benefit

- Table 74 - Proportion of Contributors to CPP (adjusted for benefit computation purposes)

- Table 75 - Average Pensionable Earnings up to YMPE (adjusted for benefit computation purposes)

- Table 76 - Average Pensionable Earnings up to YAMPE (adjusted for benefit computation purposes)

- Table 77 - Average Earnings-Related Benefit as Percentage of Maximum Benefit - Base CPP

- Table 78 - Average Additional Earnings-Related Benefit as Percentage of Maximum Additional Benefit - Additional CPP

- Table 79 - Retirement Pension Take-up Rates (2021+)

- Table 80 - New Retirement Beneficiaries and Pensions

- Table 81 - Mortality Rates of Retirement Beneficiaries

- Table 82 - Life Expectancies of Retirement Beneficiaries, with improvements after the year shown

- Table 83 - Life Expectancies of Retirement Beneficiaries by Level of Base CPP Pension (2019), with future improvements

- Table 84 - Proportion of CPP Retirement Beneficiaries who are Contributors

- Table 85 - Average Contributory Earnings of Working Beneficiaries up to the YMPE

- Table 86 - Average Contributory Earnings of Working Beneficiaries up to the YAMPE

- Table 87 - Working Beneficiaries – Contributors, Contributions, and Post-Retirement Benefits

- Table 88 - Ultimate Disability Incidence Rates (2019+)

- Table 89 - New Disability Beneficiaries

- Table 90 - New Disability Pensions and Post Retirement Disability Benefits

- Table 91 - Disability Termination Rates in 2019 and 2035

- Table 92 - Proportion of Contributors Married or in Common-Law Relationship at Time of Death

- Table 93 - New Survivor Beneficiaries

- Table 94 - New Survivor Pensions

- Table 95 - Mortality Rates of Survivor Beneficiaries

- Table 96 - Life Expectancies of Survivor Beneficiaries, with improvements after the year shown

- Table 97 - Number of Death Benefits

- Table 98 - New Children’s Benefits

- Table 99 - Operating Expenses – Base CPP

- Table 100 - Operating Expenses - Additional CPP

- Table 101 - Full Funding Rates in Respect of the Amendments to the Base CPP

- Table 102 - Additional CPP Balance Sheet (Open Group Basis, additional minimum contribution rates)

- Table 103 - Base CPP Balance Sheet (Open Group Basis)

- Table 104 - Additional CPP Balance Sheet (Open Group Basis, legislated additional contribution rates)

- Table 105 - Reconciliation of Changes in Pay-As-You-Go Rates - Base CPP

- Table 106 - Reconciliation of Changes in Minimum Contribution Rate - Base CPP

- Table 107 - Reconciliation of Changes in Additional Minimum Contribution Rates

- Table 108 - Sensitivity of the Base CPP Minimum Contribution Rate to the Investment Policy

- Table 109 - Impact of Investment Strategy on Probability of Significant Loss

- Table 110 - Investment Policy Impact on First Additional Minimum Contribution Rate

- Table 111 - Probabilities of FAMCR being within Specified Ranges as at 31 December 2048 Given Various Portfolios at Previous Valuation Date

- Table 112 - Individual Sensitivity Test Assumptions

- Table 113 - Life Expectancy in 2050 under Alternative Assumptions

- Table 114 - Sensitivity of Base CPP Minimum Contribution Rate

- Table 115 - Sensitivity of Base CPP Assets/Expenditures Ratio

- Table 116 - Sensitivity of Additional CPP Minimum Contribution Rates

- Table 117 - Sensitivity of Additional CPP Assets/Expenditures Ratio

- Table 118 - Higher and Lower Economic Growth Sensitivity Tests

- Table 119 - Younger and Older Populations Sensitivity Test Assumptions

List of charts

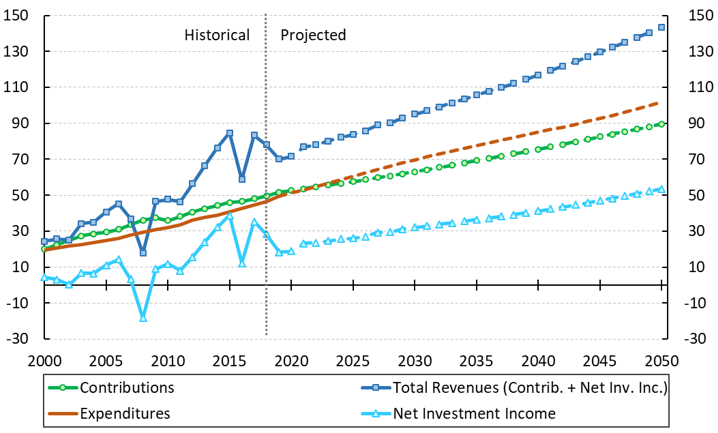

- Chart 1 - Revenues and Expenditures - Base CPP, 9.9% legislated contribution rate (2019 constant dollars)

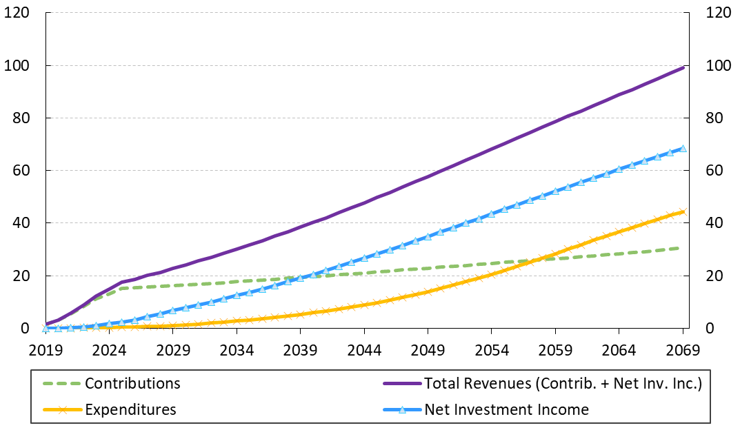

- Chart 2 - Revenues and Expenditures - Additional CPP, 2.0%/8.0% legislated contribution rates (2019 constant dollars)

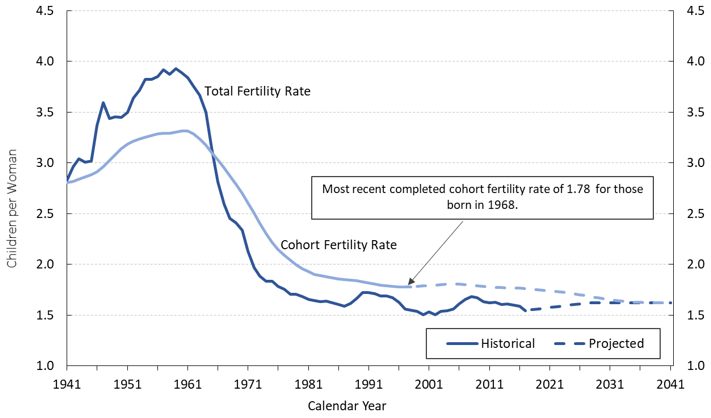

- Chart 3 - Historical and Projected Total and Cohort Fertility Rates for Canada

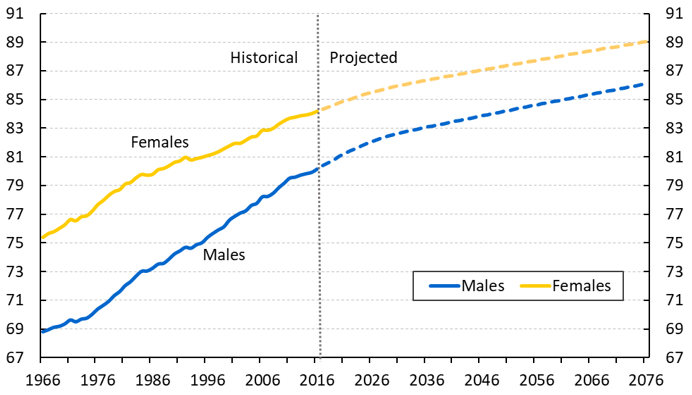

- Chart 4 - Life Expectancies at Birth for Canada, without improvements after the year shown

- Chart 5 - Life Expectancies at Age 65 for Canada, without improvements after the year shown

- Chart 6 - Net Migration Rate (Canada)

- Chart 7 - Age Distribution of the Population of Canada less Québec (thousands)

- Chart 8 - Population of Canada less Québec (millions)

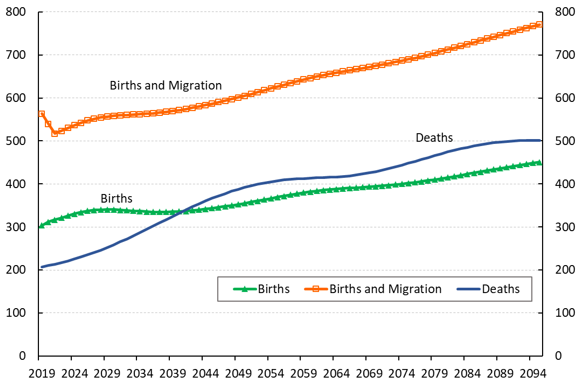

- Chart 9 - Projected Components of Population Growth for Canada less Québec (thousands)

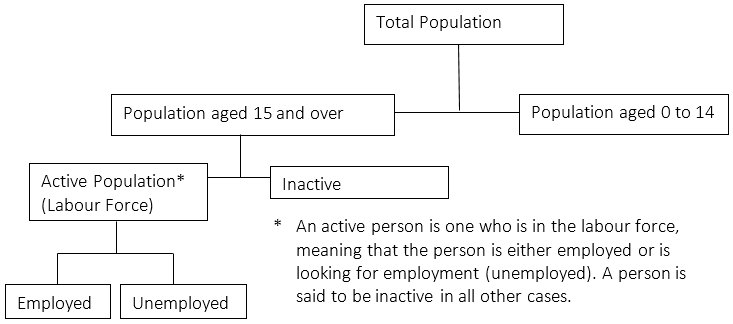

- Chart 10 - Components of the Labour Market

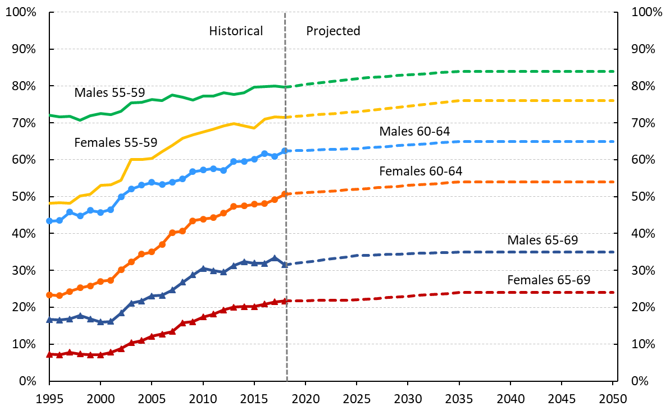

- Chart 11 - Labour Force Participation Rates (Canada)

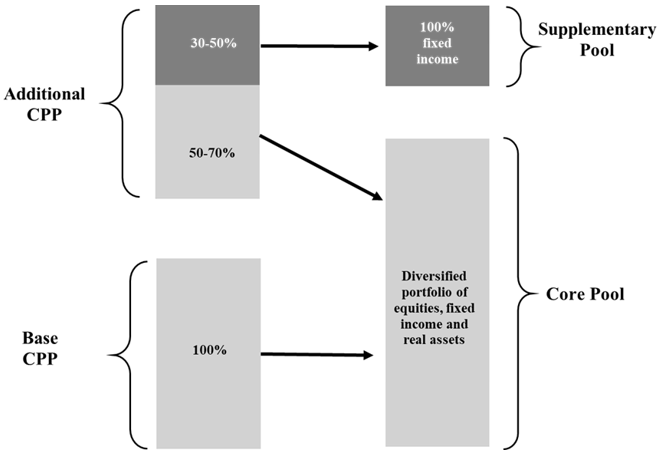

- Chart 12 - Illustrative Two-Pool Investment Structure of the CPP

- Chart 13 - Historical and Projected Retirement Pension Take-up Rates at age 60

- Chart 14 - Historical Disability Incidence Rates

- Chart 15 - Assets/Expenditures Ratio – Base CPP (legislated and minimum contribution rates)

- Chart 16 - Assets/Expenditures Ratio – Additional CPP (legislated and additional minimum contribution rates)

1. Executive Summary

1.1 Main Findings

| BASE CPP | ADDITIONAL CPP | |

|---|---|---|

|

Contributions |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expenditures |

|

|

|

Assets |

|

|

|

Minimum Contribution Rates needed to sustain the CPP |

|

|

|

||

1.2 Introduction

This is the 30th Actuarial Report on the Canada Pension Plan since the inception of the Canada Pension Plan (CPP or the Plan) in 1966. The valuation date is 31 December 2018. This report has been prepared in compliance with the timing and information requirements of the Canada Pension Plan. Section 113.1 of the Canada Pension Plan provides that the Minister of Finance and ministers of the Crown from the provinces shall review the financial state of the CPP once every three years and may consequently make recommendations to change the benefits or contribution rates, or both. Section 113.1 identifies the factors the ministers consider in their review, including information to be provided by the Chief Actuary.

As of 1 January 2019, the CPP has two components: the base and additional Plans. The CPP consisted only of the base Plan (or base CPP) prior to 2019, and this component continues. The additional Plan (or additional CPP) is the new enhancement to the CPP as of 2019. An important purpose of the report is to inform contributors and beneficiaries of the current and projected financial states of the base and additional CPP. The report provides information to evaluate the base and additional Plans’ financial sustainability over a long period, assuming that the legislation remains unchanged. Such information should facilitate a better understanding of the financial states of the base and additional Plans and the factors that influence costs, and thus contribute to an informed public discussion of issues related to the finances of the two components of the CPP.

The previous triennial report was the 27th Actuarial Report on the Canada Pension Plan as at 31 December 2015, which was tabled in the House of Commons on 27 September 2016.

The Canada Pension Plan was subject to a series of amendments since the 27th CPP Actuarial Report but prior to 31 December 2018 pursuant to the adoption of Bills C-26, C-74, and C-86. These Bills are described further in Appendix A of this report. The 28th CPP Actuarial Report was prepared to show the estimates for the Plan in respect of the introduction of the additional Plan (Bill C-26). The 29th CPP Actuarial Report was prepared to show the effect of Bill C-74 on the long-term financial states of the base and additional Plans. There was no supplemental actuarial report in respect of Bill C-86 since the cost impacts on the CPP were deemed to be small to negligible.

Under Bill C-97 – Budget Implementation Act, 2019, No. 1, the application for a CPP retirement pension is waived upon reaching age 70, effective 1 January 2020. Bill C-97 was introduced in 2019 and received Royal Assent on 21 June 2019. This amendment is considered to be a subsequent event for the purpose of this report, since it became known to the Chief Actuary after the valuation date but before the report date and was determined to have an effect on the financial state of the CPP.

In addition, amendments to the regulations regarding the calculation of the CPP contribution rates were proposed in 2018 to clarify the determination of full funding rates and introduce the calculation of the additional CPP minimum contribution rates. These regulations as well as proposed regulations regarding the sustainability of the additional CPP, namely the Calculation of Contribution Rates Regulations, 2018 and the Additional Canada Pension Plan Sustainability RegulationsFootnote 1 are awaiting formal consent by the provinces.

This 30th CPP Actuarial Report takes into account all the above listed amendments and proposed regulations as well as the subsequent event of the amendment under Bill C-97. Further, this CPP Actuarial Report takes into account the updated population estimates from Statistics Canada that became available in January 2019. This is also considered to be a subsequent event for the purpose of this report.

1.3 Independent Peer Review Process

As part of its policy of ensuring that it provides sound and relevant actuarial advice to Members of Parliament and to the Canadian population, as was done for previous reports, the Office of the Chief Actuary (OCA) has commissioned an external peer reviewFootnote 2 of this actuarial report on the CPP.

The external peer review is intended to ensure that the actuarial reports meet high professional standards, and are based on reasonable methods and assumptions. Over the years, peer review recommendations have been carefully considered and many of them implemented.

1.4 Scope of the Report

Section 2 presents a general overview of the methodology used in preparing the actuarial estimates included in this report, which are based on the best-estimate assumptions described in section 3. The results for the base Plan and additional Plan are presented separately in sections 4 and 5, respectively, and include for each component the projections of the revenues, expenditures, and assets over more than the next 75 years. Section 6 provides the reconciliation of the results for the base Plan with those of the 27th CPP Actuarial Report as well as the reconciliation of the results for the additional Plan with those of the 28th CPP Actuarial Report. Section 7 presents a general conclusion about the financial states of the base and additional Plans, and section 8 provides the actuarial opinion.

The various appendices provide a summary of the Plan provisions, a description of the data, assumptions and methodology employed, supplemental information on the financing of the CPP, detailed reconciliations of the results with previous reports, the uncertainty of results, and acknowledgements of data providers and staff who contributed to this report.

1.5 Uncertainty of Results

This actuarial report on the Canada Pension Plan presents projections of its revenues and expenditures for both of its components, the base and additional CPP, over a long period of time. Both the length of the projection period and the number of assumptions required ensure that actual future experience will not develop precisely in accordance with the best-estimate projections.

To measure the sensitivity of the long-term projected financial position of the base and additional Plans to future changes in the demographic, economic, and investment environments, a variety of sensitivity tests were performed. The tests and results are presented in detail in Appendix E of this report.

These tests show that the minimum contribution rate (MCR) of the base CPP as well as the first and second additional minimum contribution rates (FAMCR and SAMCR) of the additional Plan would deviate significantly compared to their best estimates, if other than best-estimate assumptions were realized.

Real rates of return on investments, the future evolution of mortality, and future economic growth are among the important factors that could result in the minimum contribution rates being higher than the respective legislated rates. The following table highlights some of the impacts of these factors on the MCR of the base CPP and the FAMCR and SAMCR of the additional Plan.

| Base CPP | Additional CPP |

|---|---|

| Rate of Return | |

| The 30th CPP Actuarial Report is based on an assumed nominal average 75-year rate of return of 5.95% for the base CPP and 5.38% for the additional CPP. | |

| A decrease of 1% in the assumed nominal average annual 75-year rate of return would result in: | |

|

|

| An increase of 1% in the assumed nominal average annual 75-year rate of return would result in: | |

|

|

| Given that the additional CPP relies more heavily on investment earnings as a source of revenues than the base CPP, the AMCRs are more sensitive to changes in the rate of return assumption than the MCR. | |

| Rate of Return Intervaluation Experience | |

| For the 30th CPP Actuarial Report, the assumed cumulative nominal rates of return over the inter-valuation period 2019-2021 are 16.3% for the base CPP and 8.1% for the additional CPP. | |

|

|

| Mortality | |

| The 30th CPP Actuarial Report is based on the assumption that mortality will continue to improve but at a slower pace than over the last few decades. | |

| If mortality were to improve faster than assumed with life expectancies at age 65 for males and females being about 2.4 years higher by 2050 compared to the best estimates, this would result in: | |

|

|

| If mortality is assumed to stay at the same level as in 2019, i.e. with no future improvements, this would result in: | |

|

|

| These differences represent the annual costs of increasing longevity for the base and additional Plans. | |

| Economic Growth | |

| The 30th CPP Actuarial Report is based on the assumption of moderate and sustainable economic growth. | |

| If lower economic growth is assumed with total employment earnings in 2035 being 13% lower compared to the best estimate, this would result in: | |

|

|

| If higher economic growth is assumed with total employment earnings in 2035 being 15% higher compared to the best estimate, this would result in: | |

|

|

| The impacts are in the opposite direction for the base and additional Plans due to the different financing approaches of the two components of the CPP. The base CPP relies more heavily on contributions as a source of revenues than the additional CPP. | |

Table 1.5-2 Footnotes

|

|

1.6 Conclusion

The actuarial projections of the financial states of the base and additional Plans presented in this report reveal the following.

Base CPP

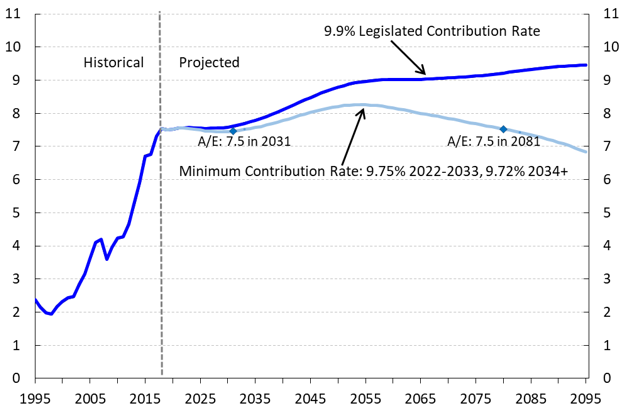

This report confirms that the legislated contribution rate of 9.9% is sufficient to finance the base CPP over the long term. Under the legislated contribution rate, contributions to the base Plan are projected to be higher than expenditures over the period 2019 to 2021, with a portion of investment income thereafter required to pay for expenditures. Total assets of the base Plan are expected to increase significantly over the next decade and then to continue increasing, but at a slower pace. Under the legislated contribution rate of 9.9%, base CPP assets are projected to accumulate to $688 billion by the end of 2030 and $1.7 trillion by 2050, while the ratio of assets to the following year’s expenditures is projected to remain relatively stable at a level of 7.6 over the period 2021 to 2031, then grow to 8.8 in 2050 and continue increasing over the projection period.

The MCR of the base CPP is 9.75% for years 2022 to 2033 and 9.72% for the year 2034 and thereafter, which is lower than the legislated contribution rate of 9.9%. Thus, despite the projected substantial increase in benefits paid as a result of an aging population, the legislated rate exceeds the MCR, and the base Plan is expected to be able to meet its obligations throughout the projection period.

Since the MCR of the base CPP is below the legislated contribution rate of 9.9%, the insufficient rates provisions in subsections 113.1(11.05) to 113.1(11.15) of the Canada Pension Plan do not apply. Therefore, in the absence of specific action by the federal and provincial governments, the legislated contribution rate will remain at 9.9% for the year 2019 and thereafter.

Additional CPP

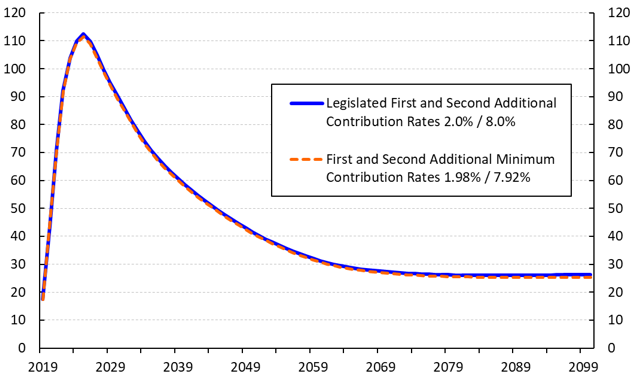

This report confirms that the legislated first and second additional contribution rates of 2.0% for 2023 and thereafter and 8.0% for 2024 and thereafter, respectively, result in projected contributions and investment income that are sufficient to fully pay the projected expenditures of the additional CPP over the long term. Under the legislated additional contribution rates, contributions to the additional Plan are projected to be higher than expenditures up to the year 2057 inclusive, with a portion of investment income thereafter required to pay for expenditures. As such, total assets of the additional Plan are expected to increase rapidly over the first several decades. Under the legislated additional contribution rates, additional CPP assets are projected to grow to $191 billion by the end of 2030 and to $1.3 trillion by 2050, while the ratio of assets to the following year’s expenditures is projected to increase rapidly until 2025 and then decrease to a level of about 26 by 2080.

The FAMCR is 1.98% for the year 2023 and thereafter, and the SAMCR is 7.92% for the year 2024 and thereafter, which are lower than the respective legislated additional contribution rates.

In accordance with the Additional Canada Pension Plan Sustainability Regulations, the AMCRs are sufficiently close to the legislated additional contribution rates such that no immediate action is required to address the differences. Therefore, in the absence of specific action by the federal and provincial governments, the legislated additional contribution rates will remain at their scheduled values.

Base and Additional CPP

To measure the sensitivity of the financial projections of each of the base and additional Plans to future changes in the demographic, economic, and investment environments, a variety of sensitivity tests were performed. Analyses of different asset allocations, the impacts of varying investment experience, and sensitivity tests on key assumptions show that the minimum contribution rates of the base and additional CPP could deviate significantly from their best-estimate values if other than best-estimate assumptions were to be realized, as shown in Appendix E of this report.

The projected financial states of the base and additional Plans presented in this report are based on the assumed demographic, economic, and investment outlooks over the long term. Given the length of the projection period and the number of assumptions required, it is unlikely that the actual experience will develop precisely in accordance with the assumptions. Therefore, it remains important to assess the financial states of the two components on a regular basis by producing periodic actuarial valuation reports. For this purpose, as required by the Canada Pension Plan, the next such actuarial valuation will be as at 31 December 2021.

2. Methodology

As of 1 January 2019, the CPP has two components: the base and additional Plans. The base Plan was the CPP prior to 2019, and this component continues. The additional Plan is the new enhancement to the CPP as of 2019. When not qualified, the term CPP or the Plan used in this report refers to the entire CPP, that is, to both its components.

The actuarial examination of the CPP involves projections of the revenues and expenditures of both components over a long period of time, so that the future impact of historical and projected trends in demographic and economic factors can be properly assessed. The actuarial estimates in this report are based on the provisions of the Canada Pension Plan as at 31 December 2018,Footnote 3 data regarding the starting point for the projections, and best-estimate assumptions regarding future demographic, economic, and investment experience.

The revenues of the base and additional Plans include both contributions and investment income. The projection of contributions begins with a projection of the working-age population. This requires assumptions regarding demographic factors such as fertility, migration, and mortality. Total contributory earnings for each component of the Plan are derived by applying labour force participation and job creation rates to the projected population and by projecting future employment earnings. This requires assumptions about various factors such as wage increases, an earnings distribution, and unemployment rates. Contributions for each of the components of the CPP are obtained by applying the respective component’s contribution rate(s) to the respective contributory earnings. Investment income is projected on the basis of the existing portfolio of assets (for the base CPP), projected net cash flows (contributions less expenditures), and the assumptions regarding the future asset mix and rates of return on investments net of investment expenses. Since the assumptions regarding the future asset mix differ between the base and additional Plans, the resulting assumptions regarding investment income differ as well.

Expenditures for each component of the Plan consist of the benefits paid out and operating expenses. Newly emerging benefits are projected by applying assumptions regarding retirement, disability, and death to the populations eligible for benefits, together with the benefit provisions and the earnings histories of participants (actual and projected). The projection of total benefits, which includes the continuation of benefits already in pay at the valuation date, requires further assumptions. Operating expenses, excluding Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) operating expenses, are projected by considering the historical and projected relationship between expenses and total employment earnings, while CPPIB operating expenses are considered in the determination of the rates of return.

The assumptions and results presented in the following sections make it possible to measure the financial states of the base and additional CPP separately in each projection year and to calculate the minimum contribution rates. For the base Plan, the minimum contribution rate (MCR) is the sum of two types of rates. The first of these excludes the full funding provision for increased or new benefits, and is referred to as the “steady-state” contribution rate. The second type of rate that makes up the MCR is the full funding rate for increased or new benefits.

For the additional CPP, there are two additional minimum contribution rates (AMCRs), the first additional minimum contribution rate (FAMCR) and the second additional minimum contribution rate (SAMCR). The FAMCR is applicable to contributory earnings below the Year’s Maximum Pensionable Earnings (YMPE) and the SAMCR is applicable to earnings between the YMPE and the Year’s Additional Maximum Pensionable Earnings (YAMPE).

Details of the methodology used to determine the MCR and AMCRs are presented in Appendix C.

A wide variety of factors influence both the current and projected financial state of the components of the CPP. Accordingly, the results shown in this report differ from those shown in previous reports. Likewise, future actuarial examinations will reveal results that differ from the projections included in this report.

3. Best-Estimate Assumptions

3.1 Introduction

The information required by statute, which is presented in sections 4 and 5 of this report, necessitates making numerous assumptions regarding future demographic, economic, and investment trends. The projections included in this report cover a long period of time (over 75 years), and the assumptions are determined by examining historical long-term and short-term trends and applying judgment as to the extent these trends will continue in the future. These assumptions reflect the Chief Actuary’s best judgment and are referred to in this report as the best-estimate assumptions. The assumptions were chosen to be independently reasonable and appropriate in the aggregate, taking into account certain interrelationships between them.

The assumptions were developed taking into account two subsequent events, that is, events that became known to the Chief Actuary after the valuation date, but before the report date, that were deemed to have an effect on the financial states of the base or additional CPP as at the valuation date. The first subsequent event is the amendment to the Plan under Bill C-97 – Budget Implementation Act, 2019, No. 1, which received Royal Assent on 21 June 2019 (application for a CPP retirement pension is waived upon reaching age 70, effective 1 January 2020). This amendment is further described in Appendices A and B of this report. The second subsequent event is the use of updated population estimates (for years 2018 and prior) from Statistics Canada that became available in January 2019.

The Chief Actuary held a seminar in September 2018 on the long-term demographic, economic, and investment outlook for Canada to obtain opinions from a wide range of individuals with relevant expertise. Five experts in the fields of demographics, economics, investments, and foresight were invited to present their views. Among the participants at the seminar were representatives from the OCA, federal departments including Statistics Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), and the Department of Finance, representatives from provincial and territorial governments, as well as representatives from Retraite Québec, the CPPIB, and other organizations. Representatives of the OCA also attended a seminar on the demographic, economic and financial outlook for 2018-2068 held by Retraite Québec in November 2018. Various presentation materials from both seminars are available on OSFI’s Web site.

Table 1 presents a summary of the most important assumptions used in this report compared with those used in the previous triennial report. The assumptions are described in more detail in Appendix B of this report.

| Canada | 30th Report (as at 31 December 2018) |

27th ReportTable footnote 1 (as at 31 December 2015) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Fertility Rate | 1.62 (2027+) | 1.65 (2019+) | ||

| Mortality | Statistics Canada Life Tables (CLT 3-year average table: 2014 – 2016) with assumed future improvements |

Canadian Human Mortality Database (CHMD 2011) with assumed future improvements |

||

| Canadian Life Expectancy at birth in 2019 at age 65 in 2019 |

Males 86.9 years 21.4 years |

Females 89.9 years 23.9 years |

Males 87.0 years 21.5 years |

Females 89.9 years 23.9 years |

| Net Migration Rate | 0.62% of population (for 2021+) | 0.62% of population (for 2016+) | ||

| Participation Rate (age group 18-69) | 79.2% | (2035) | 79.1%Table footnote 2 | (2035) |

| Employment Rate (age group 18-69) | 74.4% | (2035) | 74.4%Table footnote 2 | (2035) |

| Unemployment Rate (ages 15+) | 6.2% | (2030+) | 6.2% | (2025+) |

| Rate of Increase in Prices | 2.0% | (2019+) | 2.0% | (2017+) |

| Real Wage Increase | 1.0% | (2025+) | 1.1% | (2025+) |

| Real Rate of Return (average 2019-2093) | Base CPP Assets | 4.0% | 4.0%Table footnote 3 | |

| Additional CPP Assets | 3.4% | 3.6%Table footnote 4 | ||

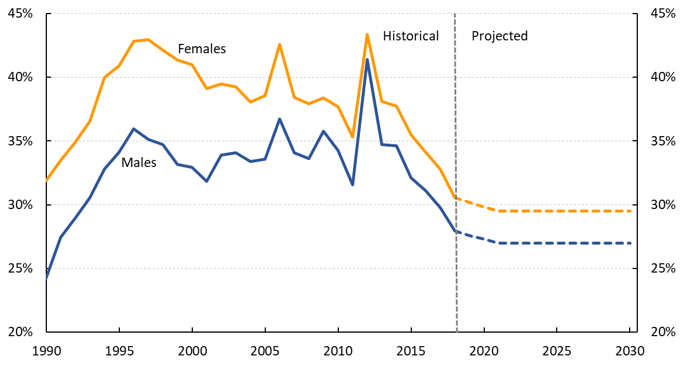

| Retirement Rates for Cohort at Age 60 | Males | 27.0% (2021+) | Males | 34.0% (2016+) |

| Females | 29.5% (2021+) | Females | 38.0% (2016+) | |

| CPP Disability Incidence Rates (per 1,000 eligible) | Males | 2.95 (2019+) | Males | 3.17 (2020+)Table footnote 5 |

| Females | 3.65 (2019+) | Females | 3.72 (2020+)Table footnote 5 | |

Table 1 Footnotes

|

||||

3.2 Demographic Assumptions

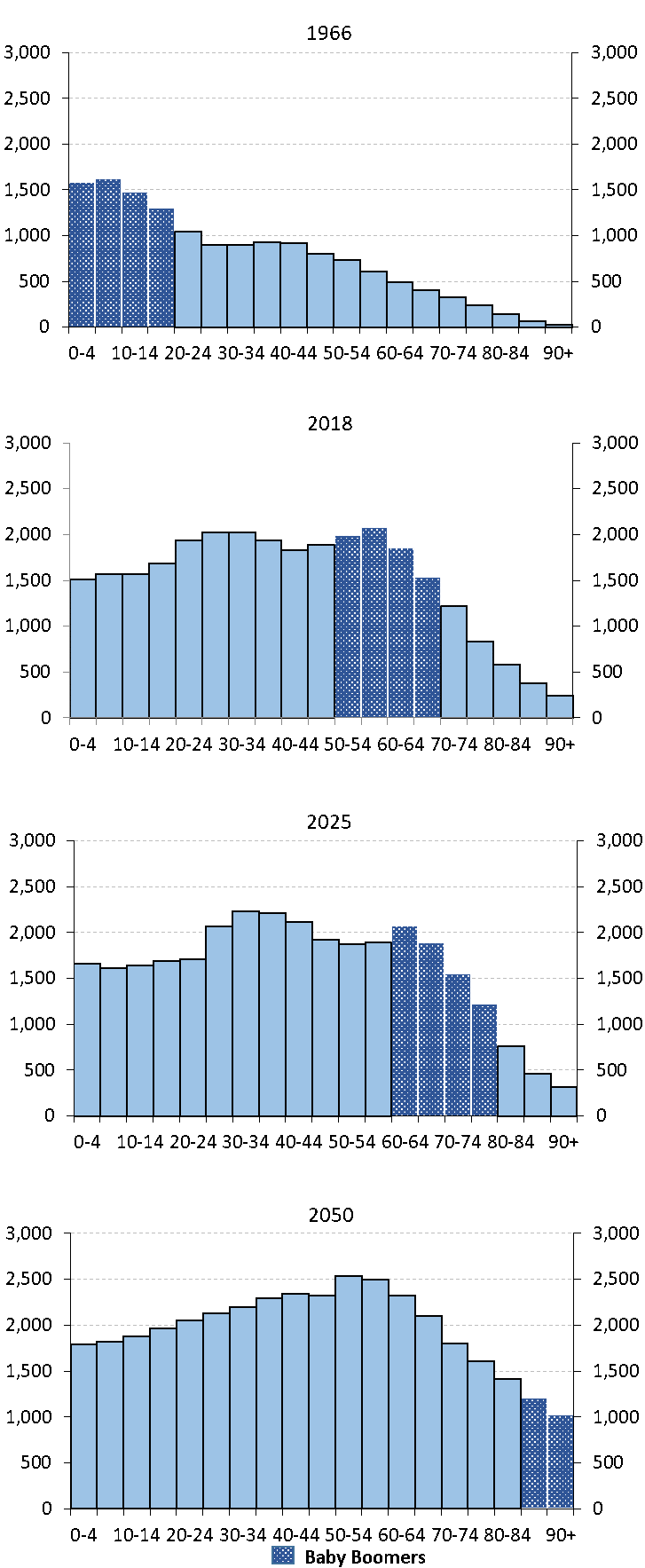

The population projections start with the Canada and Québec populations on 1 July 2018, to which are applied fertility, migration, and mortality assumptions. The relevant population for the Canada Pension Plan is the population of Canada less that of Québec and is obtained by subtracting the projected results for Québec from those for Canada. The population projections are essential in determining the future number of CPP contributors and beneficiaries.

3.2.1 Fertility

The first cause of the aging of the Canadian population is the decline in the total fertility rate that occurred during the last 50 years. The total fertility rate in Canada decreased rapidly from a level of about 4.0 children per woman in the late 1950s to 1.6 by the mid-1980s. The total fertility rate rose slightly in the early 1990s, but then declined to a level of 1.5 by the late 1990s. Canada is one of many industrialized countries that saw their fertility rates increase starting in the 2000s. By 2008, the total fertility rate for Canada reached 1.68. However, in some industrialized countries, including Canada, the total fertility rate has decreased since 2008, which could be attributable to the most recent economic downturn experienced. As of 2017, the total fertility rate for Canada stood at 1.55.Footnote 4

Similar to Canada, the total fertility rate in Québec fell from a high of about 4.0 children per woman in the 1950s; however, the Québec rate fell to a greater degree, reaching 1.4 by the mid-1980s. The Québec rate then recovered somewhat in the early 1990s to over 1.6 and subsequently declined to below 1.5 by the late 1990s. There was a significant increase in the Québec rate in the 2000s, with the rate reaching 1.74 in 2008. However, similar to Canada’s fertility rate, the fertility rate for Québec has been decreasing in recent years and stood at 1.60Footnote 4 in 2017.

The overall decrease in the total fertility rate over the last 50 years occurred as a result of changes in a variety of social, medical, and economic factors. Although there have been periods of growth in the total fertility rates in recent decades, it is unlikely that the rates will return to historical levels in the absence of significant societal changes.

The assumed age-specific fertility rates lead to an assumed total fertility rate for Canada that will increase from its 2017 level of 1.55 children per woman to an ultimate level of 1.62 in 2027. The assumed age-specific fertility rates for Québec lead to a total fertility rate for the province that will increase from its 2017 level of 1.60 to an ultimate level of 1.65 in 2027.

3.2.2 Mortality

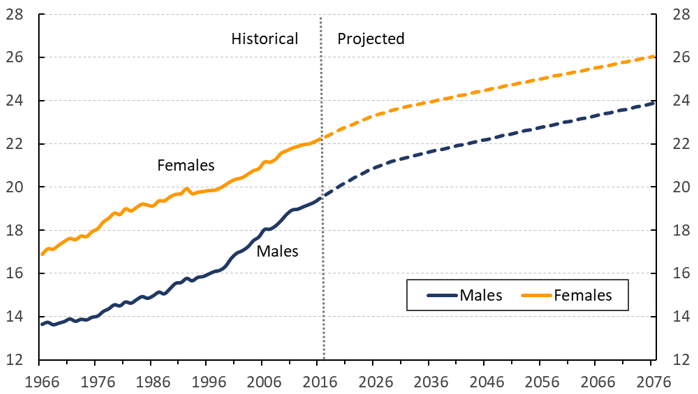

Another element that has contributed to the aging of the population is the significant reduction in the age-specific mortality rates. This can be measured by the increase in life expectancy at age 65, which directly affects how long retirement benefits will be paid to beneficiaries. Male life expectancy (without future mortality improvements, i.e. reductions in mortality) at age 65 increased by 42% between 1966 and 2015, rising from 13.6 to 19.3 years. For women, life expectancy at age 65 (without future improvements) increased by 31%, from 16.9 to 22.1 years over the same period. Although the overall gains in life expectancy at age 65 since 1966 are similar for males and females (between 5 and 6 years), about 65% of the increase occurred after 1991 for males, while for females, only about 45% of the increase occurred in that period.

Mortality improvements are expected to continue in the future, but at a slower pace than most recently observed over the 15-year period ending in 2015. Further, it is assumed that ultimately, mortality improvement rates for males will decrease to the same level as for females. The analysis of the Canadian experience over the period 1925 to 2015, including the recent slowdown trends observed in mortality improvement rates for Old Age Security (OAS) beneficiariesFootnote 5, was combined with an analysis of the possible drivers of future mortality improvements.

The 15-year average mortality improvement rates by age and sex for the period ending in 2015 are the starting point for the projected annual mortality improvement rates from 2016 onward. For ages 65 and over, the annual mortality improvement rates for 2016 to 2017 were estimated using the trends derived from the administrative data on OAS beneficiaries, representing 98% of the general population.

Starting from 2015 (2017 for ages 65 and over), the rates are assumed to gradually reduce to their ultimate levels in 2035, which are for both sexes 0.8% per year for ages below 90, 0.5% for ages 90 to 94, and 0.2% for ages 95 and above. Considering future mortality improvements, life expectancy at age 65 in 2019 is projected to be 21.4 years for males, and 23.9 years for females. This represents a decrease of 0.1 years in life expectancy at age 65 in 2019 for males and no change for females, relative to the 27th CPP Actuarial Report projections.

To project CPP benefits, the mortality rates for CPP retirement, survivor, and disability beneficiaries reflect actual experience for those segments of the population. Specific mortality experience for CPP beneficiaries is discussed further in Appendix B of this report.

3.2.3 Net Migration

Net migration corresponds to the number of immigrants less the number of emigrants, plus the number of returning Canadians and the net increase in the number of non-permanent residents.

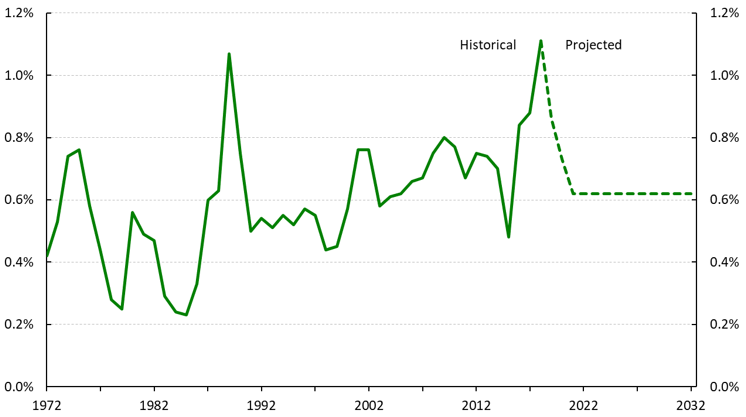

The net migration rate is expected to decrease from its current (2018) level of 1.11% of the population to 0.86% in 2019, 0.73% in 2020, and reach an ultimate level of 0.62% of the population for the year 2021 and thereafter. The ultimate net migration rate of 0.62% corresponds to the average experience observed over the last 10 years, excluding the net increase in non-permanent residents during that period. For the Québec population, the 2021 ultimate net migration rate assumption corresponds to the 10-year average historical experience for the province of 0.43%, excluding the net increase in non-permanents residents.

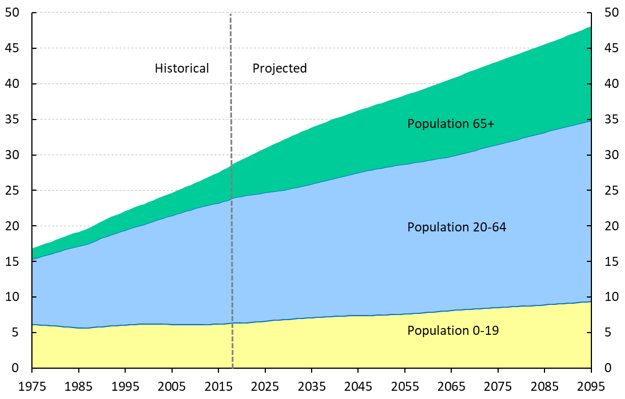

3.2.4 Population Projections

Table 2 shows the population of Canada less Québec for three age groups (0-19, 20-64 and 65 and over) throughout the projection period. The ratio of the number of people aged 20-64 to those aged 65 and over is a measure that approximates the ratio of the number of working-age people to retirees. Because of the aging population, this ratio is projected to drop from 3.6 in 2019 to about half its value or 1.9 in 2095.

| Year | Total | Age 0-19 |

Age 20-64 |

Age 65 and Over |

Ratio of 20-64 to 65 and Over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 29,025 | 6,351 | 17,707 | 4,967 | 3.6 |

| 2020 | 29,354 | 6,368 | 17,821 | 5,165 | 3.5 |

| 2021 | 29,657 | 6,389 | 17,903 | 5,365 | 3.3 |

| 2022 | 29,963 | 6,428 | 17,965 | 5,570 | 3.2 |

| 2023 | 30,272 | 6,479 | 18,013 | 5,780 | 3.1 |

| 2024 | 30,583 | 6,533 | 18,059 | 5,991 | 3.0 |

| 2025 | 30,896 | 6,596 | 18,092 | 6,208 | 2.9 |

| 2030 | 32,432 | 6,860 | 18,320 | 7,251 | 2.5 |

| 2035 | 33,841 | 7,096 | 18,825 | 7,921 | 2.4 |

| 2040 | 35,094 | 7,286 | 19,428 | 8,380 | 2.3 |

| 2045 | 36,227 | 7,382 | 20,121 | 8,724 | 2.3 |

| 2050 | 37,302 | 7,458 | 20,686 | 9,158 | 2.3 |

| 2055 | 38,381 | 7,609 | 21,099 | 9,674 | 2.2 |

| 2060 | 39,516 | 7,839 | 21,390 | 10,286 | 2.1 |

| 2065 | 40,716 | 8,093 | 21,716 | 10,907 | 2.0 |

| 2075 | 43,164 | 8,525 | 22,937 | 11,702 | 2.0 |

| 2085 | 45,555 | 8,892 | 24,291 | 12,372 | 2.0 |

| 2095 | 48,097 | 9,381 | 25,459 | 13,257 | 1.9 |

3.3 Economic and Investment Assumptions

The main economic assumptions for the Canada Pension Plan are: labour force participation rates, job creation rates, unemployment rates, the rate of increase in prices, and real increases in average employment earnings. For asset projections, further assumptions on real rates of return on invested assets are required.

One of the key elements underlying the best estimate economic assumptions relates to the continued trend toward longer working lives. Older workers are expected to exit the workforce at a later age, which could alleviate the impact of the aging of the population on future labour force growth. However, despite the expected later exit ages, labour force growth is projected to weaken as the working-age population expands at a slower pace and baby boomers exit the labour force. As a result, labour shortages together with projected improvements in productivity growth are assumed to create upward pressure on real wages until 2025.

3.3.1 Labour Force

Employment levels vary with the rate of unemployment, and reflect trends in increased workforce participation by women, longer periods of formal education among young adults, as well as changing retirement patterns of older workers.

As the population ages, older age groups with lower labour force participation increase in size. As a result, the labour force participation rate for Canadians aged 15 and over is expected to decline from 65.2% in 2019 to 63.0% in 2035. A more useful measure of the working-age population is the participation rate of those aged 18 to 69, which is expected to increase from 76.0% in 2019 to 79.2% in 2035.

The increase in the participation rate for those aged 18 to 69 is mainly due to an assumed increase in participation rates for those aged 55 and over as a result of an expected continued trend toward longer working lives. Furthermore, labour shortages create attractive employment opportunities that will continue to exert upward pressure on the participation rates for all age groups. It is also expected that future participation rates will increase with the aging of cohorts that have a stronger labour force attachment compared to previous cohorts due to higher education attainment. The cohort effect of stronger labour force attachment of women is expected to continue but at a much slower pace than in the past, resulting in a gradual narrowing of the gap between the age-specific participation rates of men and women.

As a result, the participation rates for females are projected to increase slightly more than for males. Overall, the male participation rate of those aged 18 to 69 is expected to increase from 79.8% in 2019 to 82.8% in 2035, while the female participation rate for the same age group is expected to increase from 72.1% in 2019 to 75.6% in 2035. Thereafter, the 2035 gap of 7.2% between males and females in this age group is expected to vary between 7.0% and 7.2%.

The job creation rate (i.e. the change in the number of persons employed) in Canada was on average 1.6% from 1976 to 2018 based on available employment data, and it is assumed that the rate will be 1.1% in 2019. The job creation rate assumption is determined on the basis of expected moderate economic growth and an unemployment rate for Canada, ages 15 and over, that is expected to increase from 5.8% in 2018 to 5.9% in 2019 and then reach an ultimate level of 6.2% by 2030. The assumed job creation rate for Canada, ages 15 and over, is on average about 0.7% from 2019 to 2025 and 0.6% from 2025 to 2030, which is slightly lower than the labour force growth rate. It is assumed that, starting in 2030, the job creation rate will follow the labour force growth rate, with both averaging 0.7% per year between 2030 and 2035, and 0.5% per year thereafter. The aging of the population is the main reason behind the expected slower long-term growth in the labour force and job creation rate.

3.3.2 Price Increases

Price increases, as measured by changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), tend to fluctuate from year to year. In Canada, increases in prices (inflation) was 2.3% in 2018.

In 2016, the Bank of Canada and the Government renewed their commitment to keep inflation between 1% and 3% until the end of 2021. The Senior Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada indicated in November 2018 that the Bank was undergoing an extensive review of its monetary policy framework. A number of variants to replace the inflation target are being explored. The Bank is also looking at a possible dual mandate of targeting inflation as well as GDP growth or employmentFootnote 6. Nevertheless, given the success of the 2% inflation target, it is considered very likely that the Bank will renew its inflation target commitment or that the target will at least constitute an important part of the Bank’s future mandate.

Price increase forecasts from various economists indicate an average increase in prices of 2.0% from 2019 to 2040. To reflect these forecasts and the expectation that the Bank of Canada will renew its inflation target, the price increase assumption is set at 2.0% for 2019 and thereafter.

3.3.3 Real Wage Increases

Wage increases affect the financial state of the Canada Pension Plan in two ways. In the short term, an increase in the average wage translates into higher contribution income, with little immediate impact on benefits. Over the long term, higher average wages produce higher benefits.

The difference between nominal wage increases and inflation represents increases in the real wage, which is also referred to in this report as the real wage increase. There are five main factors that influence increases in the real wage, namely general productivity, the extent to which changes in productivity are shared between labour and capital, changes in the compensation structure offered to employees, changes in the average number of hours worked, and changes in labour’s terms of tradeFootnote 7.

The real wage increase is projected to gradually rise from 0.3% in 2019 to an ultimate value of 1.0% by 2025. The ultimate real wage increase assumption is developed taking into account the relationships described above, historical trends, labour shortages, and other changes in the labour market. The ultimate real wage increase assumption combined with the ultimate price increase assumption results in an assumed annual increase in average nominal wages of 3.0% in 2025 and thereafter.

The assumptions regarding the increase in average real annual employment earnings and job creation rates result in projected average annual real increases in total Canadian employment earnings of about 1.6% for the period 2018 to 2035. After 2035, this decreases to about 1.5% on average over the remainder of the projection period, reflecting the assumed 1.0% real increase in annual wages and projected average 0.5% annual growth in the working-age population.

Given historical trends and the long-term relationship between increases in the average annual employment earnings and the YMPE, it is assumed that the nominal wage increase assumption is also applicable to the increases in the YMPE from one year to the next.

3.3.4 Real Rates of Return on Investments

Real rates of return on investments are the excess of the nominal rates of return over price increases and are required for the projection of revenue arising from investment income. A real rate of return is assumed for each year in the projection period and for each of the main asset categories in which the base and additional CPP assets are invested. The assumed long-term real rates of return on base and additional CPP assets take into account the assumed asset mixes of investments, as well as the assumed real rates of return for all categories of CPP assets. The real rates of return on investments are net of all investment expenses, including CPPIB operating expenses. The 75-year average real rate of return on the base CPP assets is assumed to be 3.95%. The additional CPP, which is assumed to have a different asset mix than the base CPP, has an expected 75-year average real rate of return of 3.38%.

For the period 2019 to 2028, the assumed annual real rates of return are lower than the assumed ultimate real rates of return in 2029 due to lower expected bond returns during the period. The average real rates of return over the period 2019-2028 for the base and additional CPP are respectively 3.6% and 2.1%. The ultimate real rates of return for the base and additional CPP are respectively 4.0% and 3.6%. Table 3 summarizes the main economic assumptions over the projection period.

| Year | Real Increase Average Annual Earnings | Real Increase Average Weekly Earnings (YMPE) | Price Increase | Labour Force (Canada) | Real Rates of Return on Investments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation Rate (Ages 15+) |

Job Creation Rate (Ages 15+) |

Unemployment Rate | Labour Force Annual Increase | Base CPP |

Additional CPP |

||||

| 2019 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 65.2 | 1.1 | 5.9 | 1.1 | 2.9 | (0.7)Table footnote 1 |

| 2020 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 65.1 | 0.8 | 5.9 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 0.4 |

| 2021 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 64.9 | 0.7 | 5.9 | 0.7 | 3.8 | 2.3 |

| 2022 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 64.7 | 0.7 | 6.0 | 0.7 | 3.6 | 2.4 |

| 2023 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 64.5 | 0.7 | 6.0 | 0.7 | 3.7 | 2.5 |

| 2024 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 64.3 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 0.7 | 3.7 | 2.6 |

| 2025 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 64.1 | 0.6 | 6.1 | 0.7 | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| 2030 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 63.2 | 0.6 | 6.2 | 0.6 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2035 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 63.0 | 0.7 | 6.2 | 0.7 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2040 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 62.5 | 0.6 | 6.2 | 0.6 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2045 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 62.2 | 0.5 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2050 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 61.9 | 0.4 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2055 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 61.5 | 0.3 | 6.2 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2060 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 61.0 | 0.3 | 6.2 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2065 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 60.5 | 0.4 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2075 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 60.2 | 0.5 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2085 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 60.1 | 0.5 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 2095 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 59.8 | 0.4 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

Table 3 Footnotes

|

|||||||||

3.4 Other Assumptions

This report is based on several other key assumptions, such as retirement benefit take-up rates and disability incidence rates.

3.4.1 Retirement Benefit Take-up Rates

The retirement benefit take-up rates are determined on a cohort basis. The sex-distinct retirement benefit take-up rate for any given age and year from age 60 and above corresponds to the number of emerging (new) retirement beneficiaries divided by the total number of people eligible for retirement benefits for the given sex, age, and year. The unreduced pension age under the Canada Pension Plan is 65. However, since 1987 a person can choose to receive a reduced retirement pension as early as age 60. This provision has had the effect of lowering the average age at pension take-up. In 1986, the average age at pension take-up was 65.2, compared to an average age of 62.5 over the decade ending in 2018.

In 2012, there was a significant increase observed in the retirement benefit take-up rates at age 60 for the cohort reaching age 60 that year. The retirement benefit take-up rates at age 60 in 2012 were 41% and 43% for males and females, respectively, compared to the corresponding rates of 32% and 35% in 2011. The observed increase in the retirement benefit take-up rates at age 60 in 2012 may have resulted from two provisions of the Economic Recovery Act (stimulus). First, the work cessation test to receive the pension early (prior to age 65) was removed in 2012. As such, starting in 2012, individuals may receive a CPP retirement pension without having to stop working or materially reduce their earnings. The removal of the work cessation test may have thus led at least in part to the observed increase in take-up rates at age 60 in 2012. Second, greater reductions in early retirement pensions were scheduled to be phased in over a five-year period, starting in 2012. The anticipation of greater adjustments may have also contributed toward the observed increase in retirement benefit take-up rates at age 60 in 2012.

After 2012, the age 60 retirement benefit take-up rates have continually decreased as the higher actuarial adjustments were phased in and the effect of the removal of the work cessation test diminished. For cohorts reaching age 60 in 2018, the retirement benefit take-up rates are 27.9% for males and 30.6% for females, which are the lowest such rates since 1992.

The retirement take-up rates at age 60 observed for 2018 are assumed to further decrease over the next three years such that, for cohorts reaching age 60 in 2021 and thereafter, the retirement benefit take-up rates are assumed to be 27.0% for males and 29.5% for females. For cohorts reaching age 65 in 2026 and thereafter, the retirement benefit take-up rates are 46.4% for both sexes. These rates result in a projected average age at retirement pension take-up in 2030 of 63.5 for males and 63.3 for females. The same retirement take–up rates apply to the additional CPP.

3.4.2 Disability Incidence Rates - Disability Pension

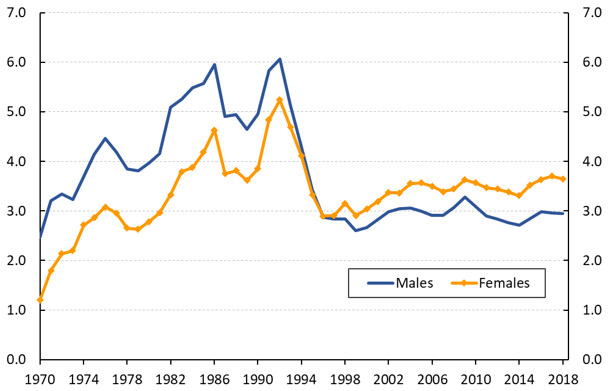

The sex-distinct disability incidence rate in respect of the disability pension at any given age is the number of new disability beneficiaries divided by the total number of people eligible for the disability pension at that age. The disability incidence rates for the base Plan are the same as for the additional Plan.

Based on the experience over the period from 2003 to 2018, the overall incidence rates for the year 2019 and thereafter are assumed to remain constant at the values in 2018, which are 2.95 per thousand eligible for males and 3.65 per thousand eligible for females.

The assumptions for the disability incidence rates in respect of the disability pension recognize that current disability incidence rates are significantly below the levels experienced from the mid-1970s to mid-1990s for males and during the early 1980s and early to mid-1990s for females. It is also recognized that incidence rates for both sexes have been relatively stable since 1997 as a result of administrative changes made to the disability program.

4. Results - Base CPP

4.1 Overview

The key observations and findings of the actuarial projections of the financial state of the base Canada Pension Plan presented in this report are as follows.

-

With the legislated contribution rate of 9.9%, contributions to the base CPP are projected to be more than sufficient to cover the expenditures over the period 2019 to 2021. Thereafter, a portion of investment income is required to make up the difference between contributions and expenditures. Between 2030 and 2050, it is projected that about 22% of investment income will be required to pay for expenditures. In 2095, it is projected that 37% of investment income will be required to cover expenditures.

-

With the legislated contribution rate of 9.9%, total assets of the base Plan are expected to increase significantly over the next decade and then will continue increasing, but at a slower pace. Total assets are expected to grow from $372 billion at the end of 2018 to $688 billion by the end of 2030. Assets are then projected to reach $1.7 trillion by 2050 and $9.9 trillion by 2095. The ratio of assets to the following year’s expenditures is projected to remain relatively stable at a level of 7.6 over the period 2021 to 2031 and then grow thereafter to values of 8.8 in 2050 and 9.5 in 2095.

-

With the legislated contribution rate of 9.9%, investment income of the base Plan, which is expected to represent 26% of revenues (i.e. contributions and investment income) in 2019, is projected to represent 37% of revenues in 2050 and 42% of revenues by 2095. This illustrates the importance of investment income as a source of revenues for the base Plan.

-

The minimum contribution rate (MCR) to sustain the base Plan is 9.75% of contributory earnings for years 2022 to 2033 and 9.72% for the year 2034 and thereafter. The legislated contribution rate of 9.9% applies to the first three years after the valuation year, that is, to the current triennial review period of 2019-2021.

-

The MCR consists of two separate components. First, the steady-state contribution rate, which is the lowest rate that results in the projected ratio of the assets to the following year’s expenditures of the base Plan remaining generally constant over the long term, before consideration of any full funding of increased or new benefits, is 9.71% for the year 2022 and thereafter. The second component is the full funding rate that is required to fully fund the recent amendments made to the Canada Pension Plan under Bill C-74 – Budget Implementation Act, 2018, No. 1. The full funding rate is 0.04% for years 2022 to 2033 and 0.01% for the year 2034 and thereafter.

-

Under the MCR, the ratio of assets to the following year’s expenditures is projected to decrease slightly from 7.6 in 2022 to 7.5 in 2031 and to be the same fifty years later in 2081.

-

The MCR determined for this report is lower than the MCR of 9.79% determined under the 27th CPP Actuarial Report. Experience over the period 2016 to 2018 was better than expected overall, especially regarding investment returns, leading to a decrease in the MCR. This decrease is partially offset by changes in assumptions. As well, the amendments under Bills C-74 and C-97 have the effects of increasing the MCR. The net result of all changes since the 27th CPP Actuarial Report is an overall absolute decrease in the MCR of 0.07% for the year 2034 and thereafter.

-

Although the pay-as-you-go rate is expected to increase over time from 9.4% in 2019 to 12.5% by 2095 due to the retirement of the baby boom generation and the projected continued aging of the population, the legislated contribution rate of 9.9% is sufficient to finance the base Plan over the long term. The pay-as-you-go rate is the contribution rate that would need to be paid if there were no assets.

-

The number of contributors to the CPP is expected to grow from 14.5 million in 2019 to 18.4 million in 2050 and 23.1 million by 2095. Under the legislated contribution rate of 9.9%, base CPP contributions are expected to increase from $51.7 billion in 2019 to $165.5 billion in 2050 and to continue increasing thereafter.

-

The number of base CPP retirement beneficiaries is expected to increase from 5.6 million in 2019 to 9.9 million in 2050 and to continue increasing thereafter.

-

There continues to be more female than male base CPP retirement beneficiaries, and by 2050 there is expected to be approximately 750,000 (or 16%) more female than male retirement beneficiaries. Thereafter, the relative difference is projected to fall.

-

Total expenditures of the base Plan are expected to grow rapidly from approximately $49.3 billion in 2019 to $86.8 billion in 2030. Thereafter, total expenditures are projected to grow at a slower pace, reaching $187.9 billion in 2050 and $1.0 trillion by 2095.

4.2 Contributions

Projected contributions are the product of the contribution rate, the number of contributors, and the average contributory earnings. The contribution rate for the base CPP is set by law and is 9.9%. As of 1 January 2019, all contributors to the base CPP also contribute to the additional CPP.

Table 4 presents the projected number of CPP contributors, including CPP retirement beneficiaries who are working (i.e. “working beneficiaries”), their base CPP contributory earnings and contributions. The number of contributors by age and sex is directly linked to the assumed labour force participation rates applied to the projected working-age population and the job creation rates. Hence, the demographic and economic assumptions have a great influence on the expected level of contributions. In this report, the number of CPP contributors is expected to increase continuously throughout the projection period, but at a generally decreasing pace, from 14.5 million in 2019 to 18.4 million in 2050 and 23.1 million by 2095. The future increase in the number of contributors is limited due to the projected lower growth in the working-age population and labour force.

The growth in base CPP contributory earnings, which are derived by subtracting the Year’s Basic Exemption (YBE) from pensionable earnings (up to the YMPE) is linked to the growth in average employment earnings through the assumption regarding annual increases in wages and is affected by the freeze on the YBE since 1998.

Contributions to the base CPP are expected to increase from $51.7 billion in 2019 to $165.5 billion in 2050 and to continue increasing thereafter, as shown in Table 4. The projected YMPE is also shown, which is assumed to increase according to the nominal wage increase assumption. The YMPE is projected to increase from $57,400 in 2019 to $67,100 in 2025 and $140,500 by 2050.

Since the legislated contribution rate is constant at 9.9% for the year 2019 and thereafter, contributions to the base CPP increase at the same rate as total contributory earnings over the projection period.

| Year | Contribution Rate (%) |

YMPE ($) |

Number of Contributors (thousands) |

Contributory Earnings ($ million) |

Contributions ($ million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 9.9 | 57,400 | 14,528 | 521,967 | 51,675 |

| 2020 | 9.9 | 58,700 | 14,712 | 542,126 | 53,670 |

| 2021 | 9.9 | 60,200 | 14,869 | 563,194 | 55,756 |

| 2022 | 9.9 | 61,800 | 15,026 | 585,498 | 57,964 |

| 2023 | 9.9 | 63,400 | 15,152 | 607,349 | 60,128 |

| 2024 | 9.9 | 65,200 | 15,274 | 630,884 | 62,458 |

| 2025 | 9.9 | 67,100 | 15,391 | 655,541 | 64,899 |

| 2030 | 9.9 | 77,800 | 15,935 | 791,884 | 78,397 |

| 2035 | 9.9 | 90,200 | 16,599 | 960,579 | 95,097 |

| 2040 | 9.9 | 104,600 | 17,201 | 1,157,737 | 114,616 |

| 2045 | 9.9 | 121,200 | 17,854 | 1,394,863 | 138,091 |

| 2050 | 9.9 | 140,500 | 18,422 | 1,671,351 | 165,464 |

| 2055 | 9.9 | 162,900 | 18,855 | 1,987,685 | 196,781 |

| 2060 | 9.9 | 188,900 | 19,214 | 2,353,547 | 233,001 |

| 2065 | 9.9 | 219,000 | 19,606 | 2,789,376 | 276,148 |

| 2075 | 9.9 | 294,300 | 20,741 | 3,973,597 | 393,386 |

| 2085 | 9.9 | 395,500 | 21,989 | 5,669,320 | 561,263 |

| 2095 | 9.9 | 531,600 | 23,126 | 8,026,025 | 794,577 |

4.3 Expenditures

The projected number of base CPP beneficiaries by type of benefit is given in Table 5, while Table 6 presents information for male and female beneficiaries separately. The number of retirement, disability, and survivor beneficiaries increases throughout the projection period. In particular, the number of retirement beneficiaries is expected to increase from 5.6 million in 2019 to 7.9 million by 2030 or by 42% due to the aging of the population and retirement of the baby boomers. By 2050, the number of retirement beneficiaries is projected to be 9.9 million. Female retirement beneficiaries continue to outnumber their male counterparts, and by 2050 there is projected to be 750,000 or 16% more female than male beneficiaries. Over the same period, the number of disability and survivor beneficiaries is projected to increase but at a much slower pace than for retirement beneficiaries.

| Year | RetirementFootnote 2,Footnote 3,Footnote 4,Footnote 5 | DisabilityFootnote 4,Footnote 6 | SurvivorFootnote 5,Footnote 6 | Children | DeathFootnote 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 5,561 | 404 | 1,292 | 218 | 159 |

| 2020 | 5,807 | 408 | 1,313 | 224 | 163 |

| 2021 | 6,017 | 412 | 1,335 | 230 | 167 |

| 2022 | 6,234 | 415 | 1,357 | 237 | 172 |

| 2023 | 6,461 | 417 | 1,380 | 244 | 176 |

| 2024 | 6,688 | 420 | 1,403 | 249 | 181 |

| 2025 | 6,913 | 421 | 1,427 | 254 | 186 |

| 2030 | 7,893 | 423 | 1,559 | 280 | 216 |

| 2035 | 8,555 | 448 | 1,703 | 309 | 252 |

| 2040 | 9,024 | 485 | 1,841 | 337 | 288 |

| 2045 | 9,442 | 526 | 1,952 | 356 | 317 |

| 2050 | 9,926 | 554 | 2,029 | 360 | 338 |

| 2055 | 10,492 | 570 | 2,074 | 359 | 351 |

| 2060 | 11,122 | 573 | 2,099 | 358 | 357 |

| 2065 | 11,686 | 574 | 2,128 | 364 | 363 |

| 2075 | 12,554 | 618 | 2,256 | 383 | 395 |

| 2085 | 13,316 | 671 | 2,395 | 397 | 433 |

| 2095 | 14,269 | 705 | 2,432 | 408 | 447 |

Table 5 Footnotes

|

|||||

| Year | Males | Females | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetirementFootnote 2,Footnote 3,Footnote 4,Footnote 5 | DisabilityFootnote 4,Footnote 6 | SurvivorFootnote 5,Footnote 6 | DeathFootnote 7 | RetirementFootnote 2,Footnote 3,Footnote 4,Footnote 5 | DisabilityFootnote 4,Footnote 6 | SurvivorFootnote 5,Footnote 6 | DeathFootnote 7 | |

| 2019 | 2,688 | 183 | 251 | 95 | 2,872 | 221 | 1,042 | 65 |

| 2020 | 2,797 | 184 | 259 | 97 | 3,010 | 224 | 1,054 | 67 |

| 2021 | 2,894 | 185 | 268 | 98 | 3,124 | 227 | 1,067 | 69 |

| 2022 | 2,993 | 186 | 277 | 100 | 3,241 | 229 | 1,080 | 71 |

| 2023 | 3,098 | 187 | 285 | 103 | 3,364 | 231 | 1,094 | 74 |

| 2024 | 3,202 | 187 | 294 | 105 | 3,486 | 232 | 1,109 | 76 |

| 2025 | 3,305 | 187 | 303 | 107 | 3,608 | 234 | 1,124 | 79 |

| 2030 | 3,747 | 186 | 346 | 122 | 4,147 | 238 | 1,213 | 95 |

| 2035 | 4,023 | 194 | 386 | 139 | 4,533 | 253 | 1,317 | 113 |

| 2040 | 4,200 | 210 | 416 | 154 | 4,824 | 274 | 1,424 | 133 |

| 2045 | 4,364 | 229 | 436 | 166 | 5,078 | 296 | 1,516 | 151 |

| 2050 | 4,588 | 243 | 446 | 174 | 5,338 | 311 | 1,582 | 164 |

| 2055 | 4,881 | 250 | 452 | 178 | 5,611 | 321 | 1,622 | 173 |

| 2060 | 5,224 | 249 | 458 | 180 | 5,898 | 324 | 1,641 | 177 |

| 2065 | 5,525 | 247 | 467 | 183 | 6,161 | 327 | 1,662 | 179 |

| 2075 | 5,950 | 267 | 489 | 201 | 6,604 | 352 | 1,767 | 194 |

| 2085 | 6,316 | 290 | 500 | 220 | 7,000 | 381 | 1,895 | 213 |

| 2095 | 6,789 | 305 | 501 | 224 | 7,480 | 400 | 1,931 | 222 |

Table 6 Footnotes

|

||||||||

Table 7 shows the amount of projected base CPP expenditures by type. Total expenditures of the base Plan are expected to grow rapidly from approximately $49.3 billion in 2019 to $86.8 billion in 2030. Thereafter, total expenditures are projected to grow at a slower pace, reaching $187.9 billion in 2050. Table 8 shows the same information but in millions of 2019 constant dollars.

Table 9 shows the projected base CPP expenditures by type expressed as a percentage of contributory earnings. These are referred to as the pay-as-you-go (or “PayGo”) rates. A pay-as-you-go rate corresponds to the contribution rate that would need to be paid if there were no assets. Although the total pay-as-you-go rate is expected to increase significantly from 9.4% in 2019 to 12.5% by the end of the projection period, the legislated contribution rate of 9.9% is sufficient to finance the base Plan over the projection period.

| Year | RetirementFootnote 1 | DisabilityFootnote 2 | Survivor | Children | Death | Operating ExpensesFootnote 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 38,541 | 4,363 | 4,802 | 528 | 398 | 659 | 49,291 |

| 2020 | 41,228 | 4,498 | 4,899 | 554 | 408 | 683 | 52,270 |

| 2021 | 43,665 | 4,630 | 5,002 | 582 | 418 | 707 | 55,004 |

| 2022 | 46,369 | 4,756 | 5,109 | 611 | 429 | 733 | 58,007 |

| 2023 | 49,249 | 4,876 | 5,222 | 642 | 441 | 759 | 61,188 |

| 2024 | 52,295 | 5,007 | 5,342 | 669 | 453 | 786 | 64,551 |

| 2025 | 55,472 | 5,131 | 5,472 | 696 | 466 | 814 | 68,052 |

| 2026 | 58,730 | 5,257 | 5,614 | 724 | 479 | 843 | 71,648 |

| 2027 | 62,031 | 5,385 | 5,769 | 753 | 493 | 874 | 75,305 |

| 2028 | 65,391 | 5,513 | 5,938 | 784 | 508 | 905 | 79,039 |

| 2029 | 68,811 | 5,655 | 6,123 | 816 | 524 | 937 | 82,867 |

| 2030 | 72,245 | 5,820 | 6,326 | 850 | 540 | 971 | 86,752 |

| 2031 | 75,652 | 6,021 | 6,546 | 885 | 557 | 1,006 | 90,667 |

| 2032 | 79,012 | 6,248 | 6,785 | 920 | 574 | 1,043 | 94,583 |

| 2033 | 82,362 | 6,494 | 7,040 | 957 | 593 | 1,081 | 98,526 |

| 2034 | 85,757 | 6,755 | 7,313 | 996 | 611 | 1,121 | 102,553 |

| 2035 | 89,223 | 7,029 | 7,603 | 1,038 | 629 | 1,163 | 106,684 |

| 2036 | 92,768 | 7,314 | 7,909 | 1,080 | 647 | 1,204 | 110,922 |

| 2037 | 96,357 | 7,625 | 8,231 | 1,122 | 665 | 1,247 | 115,248 |

| 2038 | 99,979 | 7,962 | 8,568 | 1,166 | 684 | 1,293 | 119,651 |

| 2039 | 103,674 | 8,322 | 8,920 | 1,210 | 701 | 1,340 | 124,167 |

| 2040 | 107,497 | 8,693 | 9,285 | 1,254 | 718 | 1,388 | 128,835 |

| 2041 | 111,464 | 9,080 | 9,662 | 1,296 | 734 | 1,439 | 133,676 |

| 2042 | 115,578 | 9,483 | 10,050 | 1,338 | 750 | 1,492 | 138,691 |

| 2043 | 119,867 | 9,900 | 10,448 | 1,378 | 765 | 1,547 | 143,907 |

| 2044 | 124,366 | 10,327 | 10,858 | 1,418 | 780 | 1,605 | 149,353 |

| 2045 | 129,101 | 10,757 | 11,276 | 1,456 | 792 | 1,663 | 155,045 |

| 2046 | 134,106 | 11,189 | 11,702 | 1,491 | 804 | 1,724 | 161,016 |

| 2047 | 139,395 | 11,622 | 12,135 | 1,525 | 816 | 1,787 | 167,279 |

| 2048 | 144,971 | 12,056 | 12,575 | 1,559 | 826 | 1,851 | 173,838 |

| 2049 | 150,859 | 12,495 | 13,021 | 1,592 | 836 | 1,917 | 180,720 |

| 2050 | 157,090 | 12,932 | 13,472 | 1,624 | 844 | 1,984 | 187,948 |

| 2055 | 193,653 | 15,126 | 15,781 | 1,783 | 876 | 2,349 | 229,568 |

| 2060 | 240,078 | 17,272 | 18,239 | 1,969 | 891 | 2,769 | 281,218 |

| 2065 | 294,776 | 19,706 | 21,144 | 2,209 | 905 | 3,267 | 342,009 |

| 2070 | 355,890 | 23,218 | 24,885 | 2,505 | 937 | 3,874 | 411,310 |

| 2075 | 427,008 | 27,465 | 29,737 | 2,837 | 987 | 4,619 | 492,653 |

| 2080 | 510,241 | 32,551 | 35,628 | 3,196 | 1,040 | 5,509 | 588,165 |

| 2085 | 609,556 | 38,607 | 42,324 | 3,578 | 1,083 | 6,563 | 701,711 |

| 2090 | 731,717 | 45,267 | 49,594 | 3,997 | 1,108 | 7,804 | 839,487 |

| 2095 | 881,259 | 52,698 | 57,461 | 4,482 | 1,116 | 9,264 | 1,006,280 |

Table 7 Footnotes

|

|||||||

| Year | RetirementFootnote 2 | DisabilityFootnote 3 | Survivor | Children | Death | Operating ExpensesFootnote 4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 38,541 | 4,363 | 4,802 | 528 | 398 | 659 | 49,291 |

| 2020 | 40,419 | 4,410 | 4,803 | 543 | 400 | 670 | 51,245 |

| 2021 | 41,969 | 4,450 | 4,808 | 559 | 402 | 680 | 52,868 |

| 2022 | 43,694 | 4,482 | 4,814 | 576 | 404 | 691 | 54,661 |

| 2023 | 45,499 | 4,504 | 4,824 | 593 | 407 | 701 | 56,528 |

| 2024 | 47,365 | 4,535 | 4,838 | 606 | 410 | 712 | 58,466 |

| 2025 | 49,258 | 4,556 | 4,859 | 618 | 414 | 723 | 60,428 |

| 2026 | 51,128 | 4,576 | 4,888 | 630 | 417 | 734 | 62,373 |

| 2027 | 52,943 | 4,596 | 4,924 | 643 | 421 | 746 | 64,272 |

| 2028 | 54,716 | 4,613 | 4,969 | 656 | 425 | 757 | 66,136 |

| 2029 | 56,449 | 4,639 | 5,023 | 670 | 430 | 769 | 67,980 |

| 2030 | 58,104 | 4,681 | 5,088 | 684 | 435 | 781 | 69,772 |

| 2031 | 59,651 | 4,748 | 5,162 | 698 | 439 | 793 | 71,490 |

| 2032 | 61,079 | 4,830 | 5,245 | 712 | 444 | 806 | 73,116 |

| 2033 | 62,420 | 4,921 | 5,335 | 725 | 449 | 819 | 74,671 |

| 2034 | 63,718 | 5,019 | 5,433 | 740 | 454 | 833 | 76,198 |

| 2035 | 64,994 | 5,120 | 5,538 | 756 | 458 | 847 | 77,714 |

| 2036 | 66,251 | 5,224 | 5,648 | 771 | 462 | 860 | 79,216 |

| 2037 | 67,465 | 5,339 | 5,763 | 786 | 466 | 873 | 80,692 |

| 2038 | 68,628 | 5,465 | 5,882 | 800 | 469 | 887 | 82,132 |

| 2039 | 69,770 | 5,600 | 6,003 | 814 | 472 | 902 | 83,561 |

| 2040 | 70,924 | 5,735 | 6,126 | 827 | 474 | 916 | 85,002 |

| 2041 | 72,099 | 5,873 | 6,250 | 839 | 475 | 931 | 86,467 |

| 2042 | 73,294 | 6,014 | 6,373 | 848 | 476 | 946 | 87,952 |

| 2043 | 74,524 | 6,155 | 6,496 | 857 | 476 | 962 | 89,470 |

| 2044 | 75,805 | 6,295 | 6,618 | 864 | 475 | 978 | 91,035 |

| 2045 | 77,148 | 6,428 | 6,739 | 870 | 474 | 994 | 92,652 |

| 2046 | 78,568 | 6,555 | 6,856 | 874 | 471 | 1,010 | 94,333 |

| 2047 | 80,065 | 6,675 | 6,970 | 876 | 468 | 1,026 | 96,081 |

| 2048 | 81,635 | 6,789 | 7,081 | 878 | 465 | 1,042 | 97,890 |

| 2049 | 83,285 | 6,898 | 7,188 | 879 | 461 | 1,058 | 99,770 |

| 2050 | 85,025 | 6,999 | 7,292 | 879 | 457 | 1,074 | 101,726 |

| 2055 | 94,933 | 7,415 | 7,736 | 874 | 429 | 1,152 | 112,540 |

| 2060 | 106,597 | 7,669 | 8,098 | 874 | 396 | 1,230 | 124,864 |

| 2065 | 118,545 | 7,925 | 8,503 | 889 | 364 | 1,314 | 137,540 |

| 2070 | 129,630 | 8,457 | 9,064 | 912 | 341 | 1,411 | 149,817 |

| 2075 | 140,873 | 9,061 | 9,810 | 936 | 326 | 1,524 | 162,529 |

| 2080 | 152,463 | 9,726 | 10,646 | 955 | 311 | 1,646 | 175,747 |

| 2085 | 164,969 | 10,449 | 11,455 | 968 | 293 | 1,776 | 189,910 |

| 2090 | 179,362 | 11,096 | 12,157 | 980 | 271 | 1,913 | 205,779 |

| 2095 | 195,655 | 11,700 | 12,757 | 995 | 248 | 2,057 | 223,412 |

Table 8 Footnotes

|

|||||||

| Year | RetirementFootnote 1 | DisabilityFootnote 2 | Survivor | Children | Death | Operating ExpensesFootnote 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 7.38 | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 9.44 |

| 2020 | 7.60 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 9.64 |

| 2021 | 7.75 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 9.77 |

| 2022 | 7.92 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 9.91 |

| 2023 | 8.11 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 10.07 |

| 2024 | 8.29 | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 10.23 |

| 2025 | 8.46 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 10.38 |

| 2026 | 8.63 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 10.53 |

| 2027 | 8.77 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 10.65 |

| 2028 | 8.91 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 10.77 |

| 2029 | 9.03 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 10.87 |

| 2030 | 9.12 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 10.96 |

| 2031 | 9.20 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 11.02 |

| 2032 | 9.24 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 11.06 |

| 2033 | 9.27 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 11.09 |

| 2034 | 9.28 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 11.10 |

| 2035 | 9.29 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 11.11 |

| 2036 | 9.31 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.13 |

| 2037 | 9.31 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.14 |

| 2038 | 9.31 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.14 |

| 2039 | 9.30 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.14 |

| 2040 | 9.29 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.13 |

| 2041 | 9.28 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.13 |

| 2042 | 9.27 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.12 |

| 2043 | 9.25 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.11 |

| 2044 | 9.25 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.11 |

| 2045 | 9.26 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.12 |

| 2046 | 9.26 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 11.12 |

| 2047 | 9.29 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 11.14 |

| 2048 | 9.31 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 11.17 |

| 2049 | 9.35 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 11.20 |

| 2050 | 9.40 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 11.25 |

| 2055 | 9.74 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 11.55 |

| 2060 | 10.20 | 0.73 | 0.77 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 11.95 |

| 2065 | 10.57 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 12.26 |

| 2070 | 10.71 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 12.37 |

| 2075 | 10.75 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 12.40 |

| 2080 | 10.74 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 12.38 |

| 2085 | 10.75 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 12.38 |

| 2090 | 10.84 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 12.44 |

| 2095 | 10.98 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 12.54 |

Table 9 Footnotes

|

|||||||

4.4 Financial Projections with Legislated Contribution Rate

4.4.1 Market Value of Assets as at 31 December 2018