Actuarial Report (16th) on the Old Age Security Program

Accessibility statement

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) defines requirements for designers and developers to improve accessibility for people with disabilities. It defines three levels of conformance: Level A, Level AA, and Level AAA. This report is partially conformant with WCAG 2.0 level AA. If you require a compliant version, please contact webmaster@osfi-bsif.gc.ca.

The Honourable Deb Schulte, P.C., M.P. Minister of Seniors

House of Commons

Ottawa, Canada

K1A 0A6

Dear Minister:

In accordance with section 3 of the Public Pensions Reporting Act, I am pleased to submit the Actuarial Report prepared as at 31 December 2018, on the pension plan established under the Old Age Security Act.

Yours sincerely,

Assia Billig, FCIA, FSA, PhD

Chief Actuary

Table of contents

List of Tables

- Table 1 Best-Estimate Assumptions

- Table 2 Population of Canada

- Table 3 Economic Assumptions

- Table 4 Recipient Rates

- Table 5 Beneficiaries (historical)

- Table 6 Beneficiaries (projected)

- Table 7 Expenditures and Average Annual Benefit (historical)

- Table 8 Expenditures and Average Annual Benefit (projected)

- Table 9 Expenditures as Percentage of GDP (historical)

- Table 10 Expenditures as Percentage of GDP (projected)

- Table 11 Expenditures as Percentage of Total Employment Earnings (historical)

- Table 12 Expenditures as Percentage of Total Employment Earnings (projected)

- Table 13 Financial Results - Totals for 2016 to 2018

- Table 14 Reconciliation of Expenditures as a Percentage of GDP

- Table 15 Individual Sensitivity Test Assumptions

- Table 16 Life Expectancy in 2050 under Alternative Assumption

- Table 17 Sensitivity Test Results

- Table 18 Higher and Lower Economic Growth Sensitivity Tests

- Table 19 Younger and Older Populations Sensitivity Test Assumptions

- Table 20 Detailed Reconciliation of Expenditures as a Percentage of GDP

- Table 21 Cohort Fertility Rates by Age and Year of Birth

- Table 22 Fertility Rates for Canada

- Table 23 Annual Mortality Improvement Rates for Canada

- Table 24 Mortality Rates for Canada

- Table 25 Life Expectancies for Canada, without improvements after the year shown

- Table 26 Life Expectancies for Canada, with improvements after the year shown

- Table 27 Population of Canada by Age

- Table 28 Analysis of Population of Canada by Age

- Table 29 Births, Net Migrants, and Deaths for Canada

- Table 30 Active Population (Canada, ages 15 and over)

- Table 31 Labour Force Participation, Employment, and Unemployment Rates

- Table 32 Labour Force Participation Rates (Canada)

- Table 33 Employment of Population

- Table 34 Real Wage Increase and Related Components

- Table 35 Inflation, Real AAE and AWE Increases

- Table 36 Assumed Deferral Rates for Cohorts Reaching Age 65 in 2019 and Thereafter

- Table 37 OAS Basic Pension Recipient Rates by Age

- Table 38 OAS Basic Pension Recipient Rates by Age, Sex, and Level of Benefit

- Table 39 OAS Beneficiaries Affected by the OAS Recovery Tax

- Table 40 Financial Impact of OAS Recovery Tax

- Table 41 GIS and Allowance Recipient Rates

- Table 42 Impact of Additional CPP on GIS Beneficiaries and Expenditures

- Table 43 Projected Maximum Monthly Benefits

- Table 44 Average Benefits as Percentage of Maximum Rates

- Table 45 Experience Adjustment Factors

- Table 46 OAS Basic Benefit Beneficiaries

- Table 47 OAS Basic Benefit Expenditures

- Table 48 GIS Beneficiaries (Total)

- Table 49 GIS Expenditures (Total)

- Table 50 GIS Beneficiaries (Single)

- Table 51 GIS Expenditures (Single)

- Table 52 GIS Beneficiaries (Spouse a Pensioner)

- Table 53 GIS Expenditures (Spouse a Pensioner)

- Table 54 GIS Beneficiaries (Spouse Not a Pensioner)

- Table 55 GIS Expenditures (Spouse Not a Pensioner)

- Table 56 GIS Beneficiaries (Spouse with Allowance)

- Table 57 GIS Expenditures (Spouse with Allowance)

- Table 58 Allowance Beneficiaries (Total)

- Table 59 Allowance Expenditures (Total)

- Table 60 Allowance Beneficiaries (Regular)

- Table 61 Allowance Expenditures (Regular)

- Table 62 Allowance Beneficiaries (Survivor)

- Table 63 Allowance Expenditures (Survivor)

List of Charts

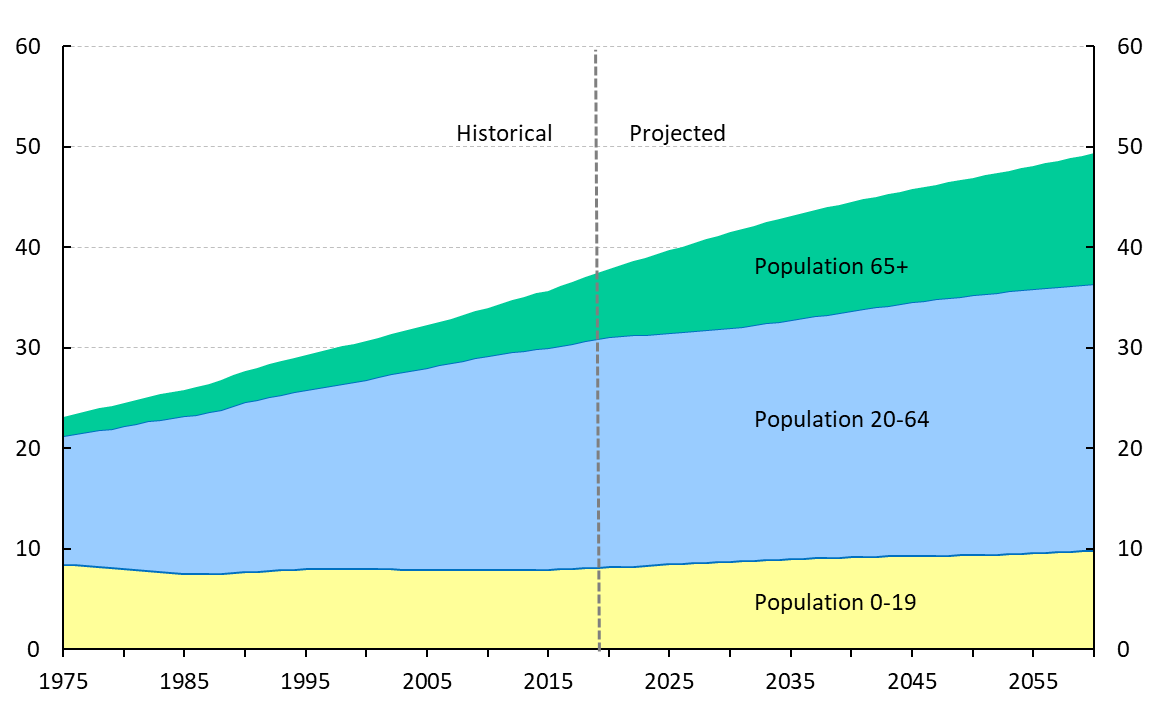

- Chart 1 Analysis of Population of Canada by Age Group

- Chart 2 Expenditures as a Proportion of GDP

- Chart 3 Historical and Projected Total and Cohort Fertility Rates for Canada

- Chart 4 Life Expectancies at Age 65 for Canada, without improvements after

the year shown - Chart 5 Net Migration Rate (Canada)

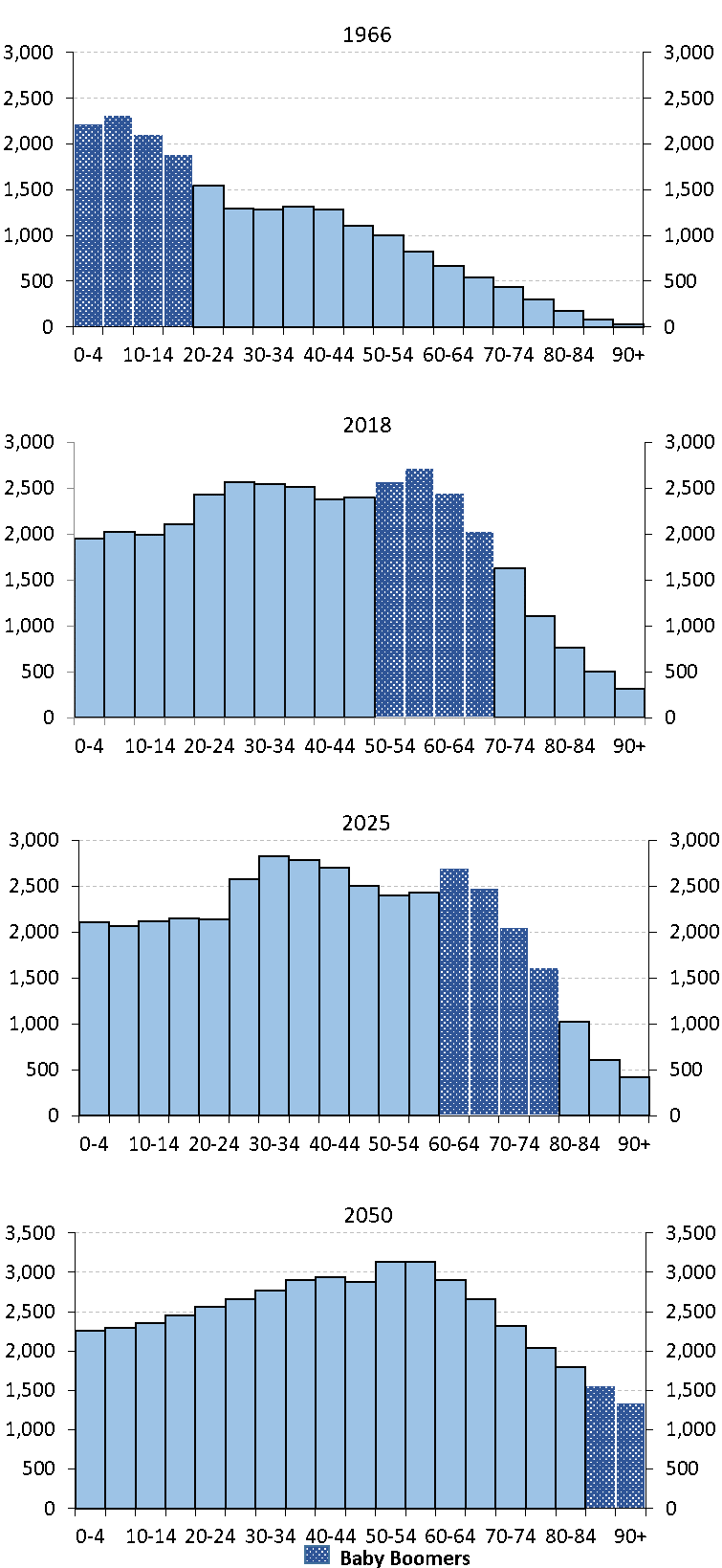

- Chart 6 Age Distribution of the Canadian Population

- Chart 7 Population of Canada

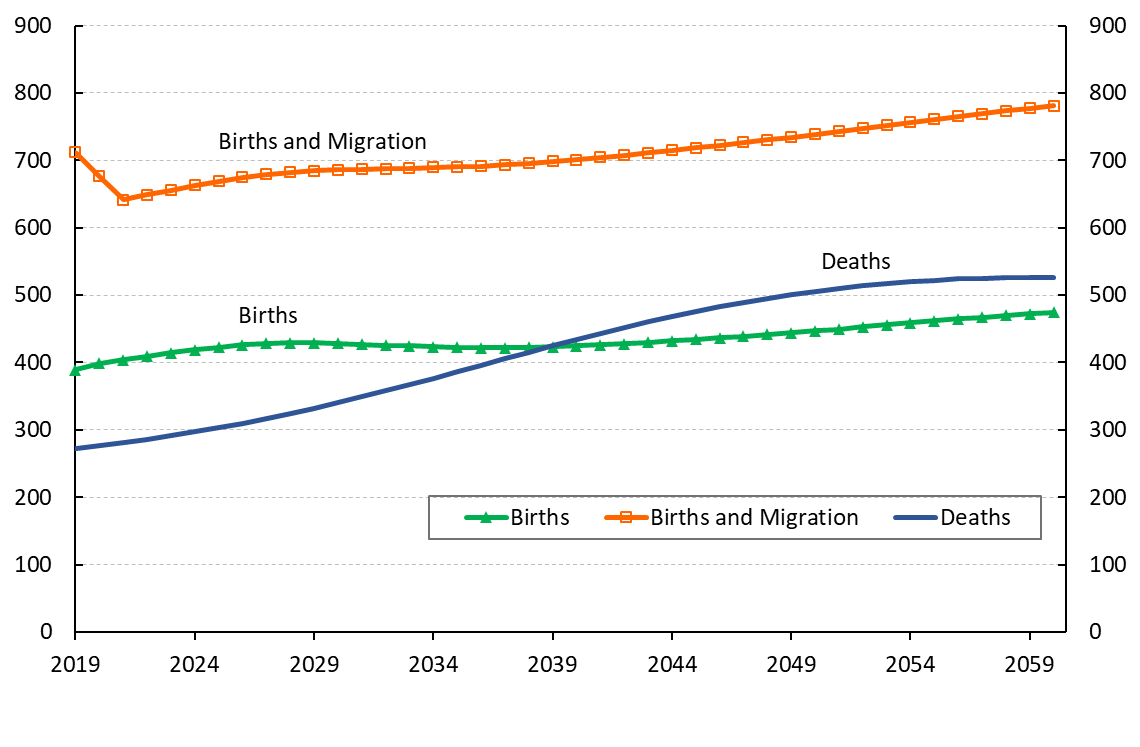

- Chart 8 Projected Components of Population Growth for Canada

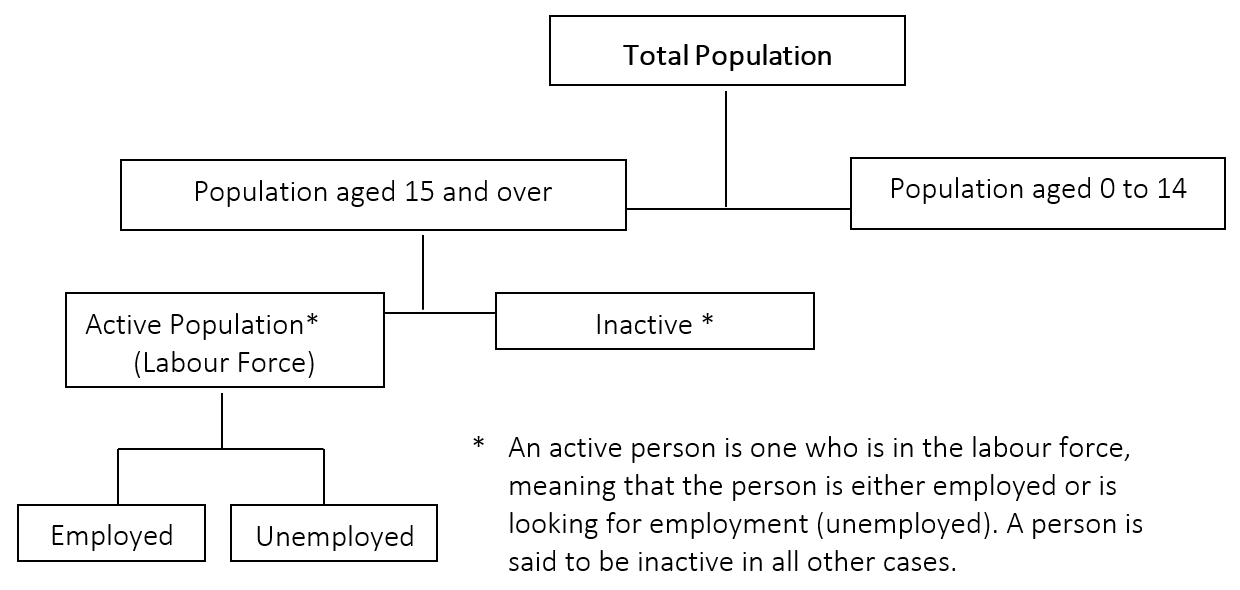

- Chart 9 Components of the Labour Market

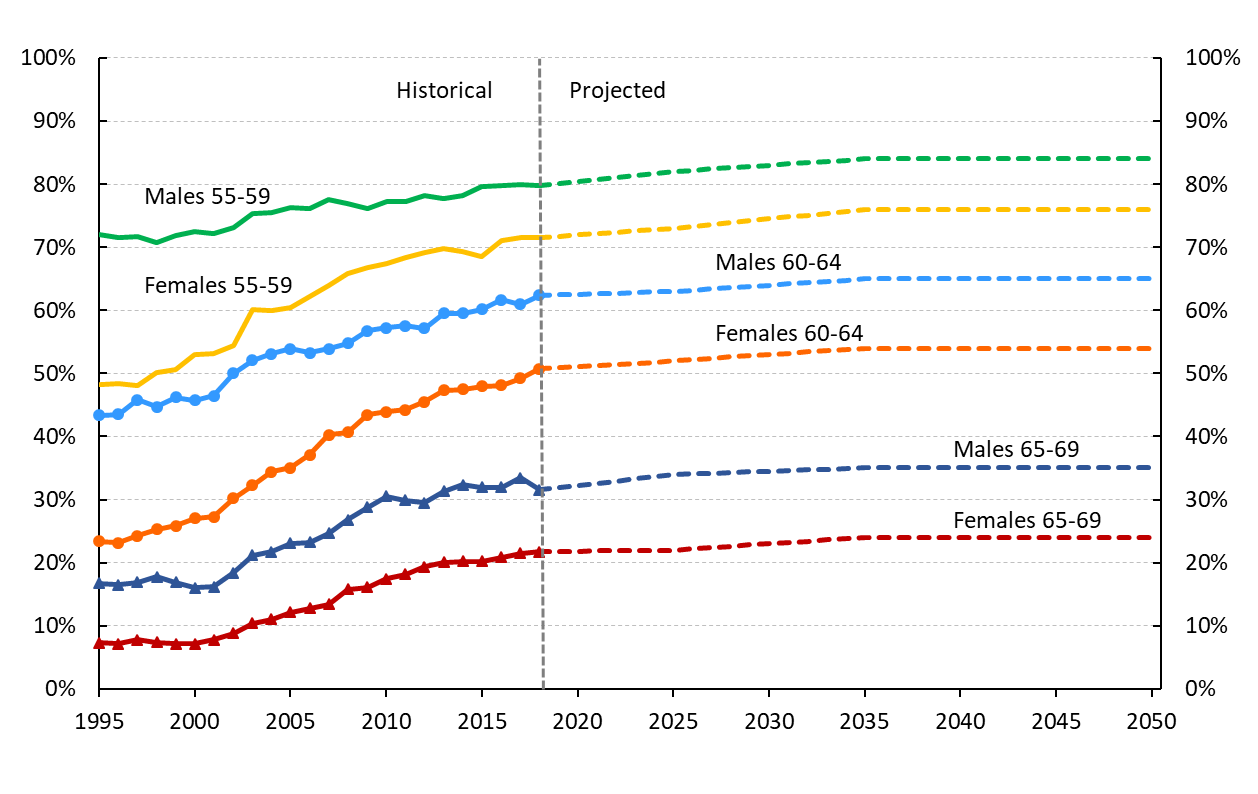

- Chart 10 Labour Force Participation Rates (Canada)

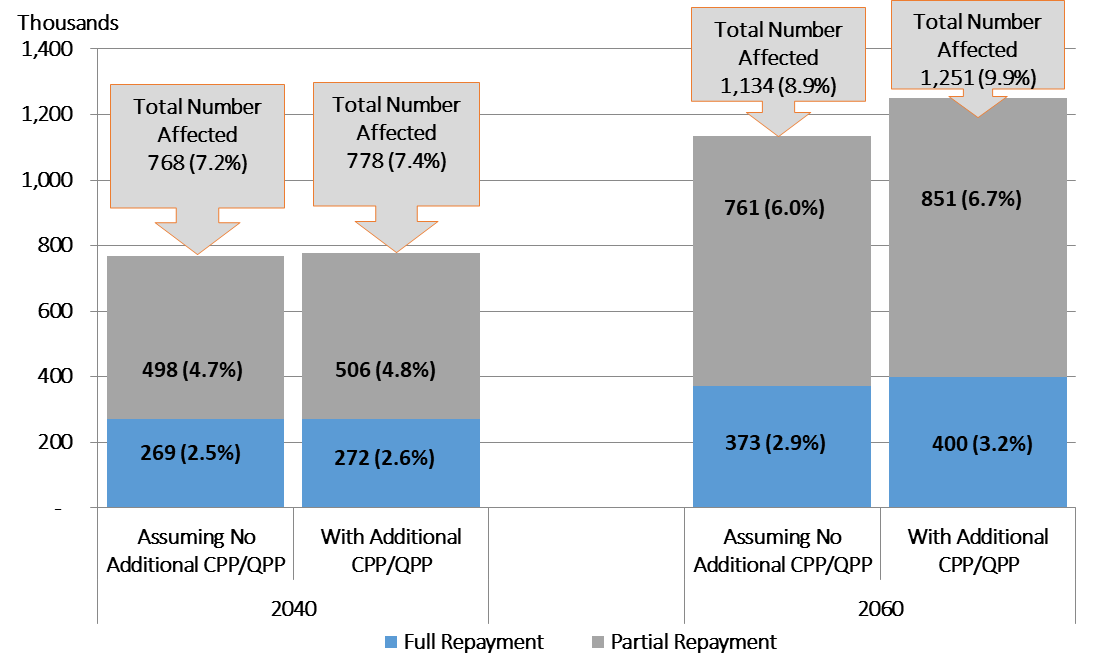

- Chart 11 Impact of Additional CPP and QPP on OAS Beneficiaries Affected by Recovery Tax (number in 000s and % affected)

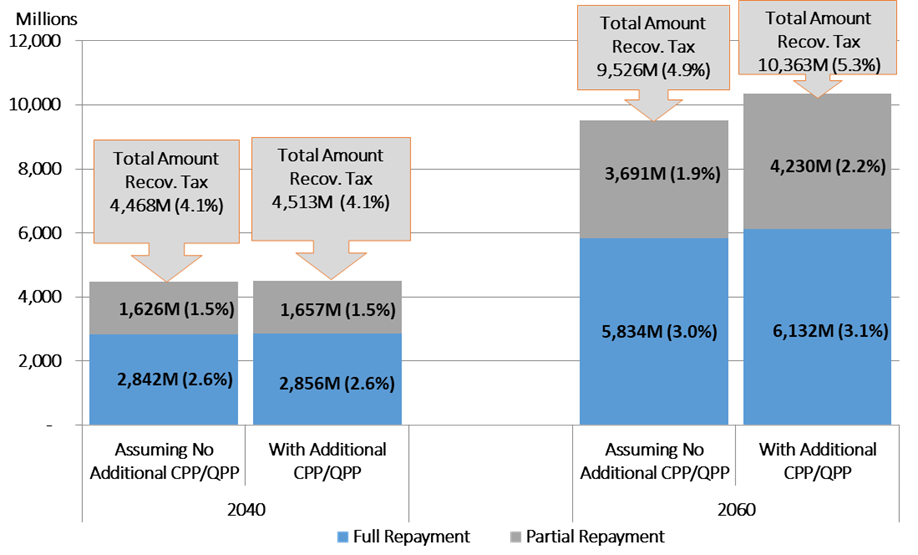

- Chart 12 Impact of Additional CPP and QPP on Amount of OAS Recovery Tax

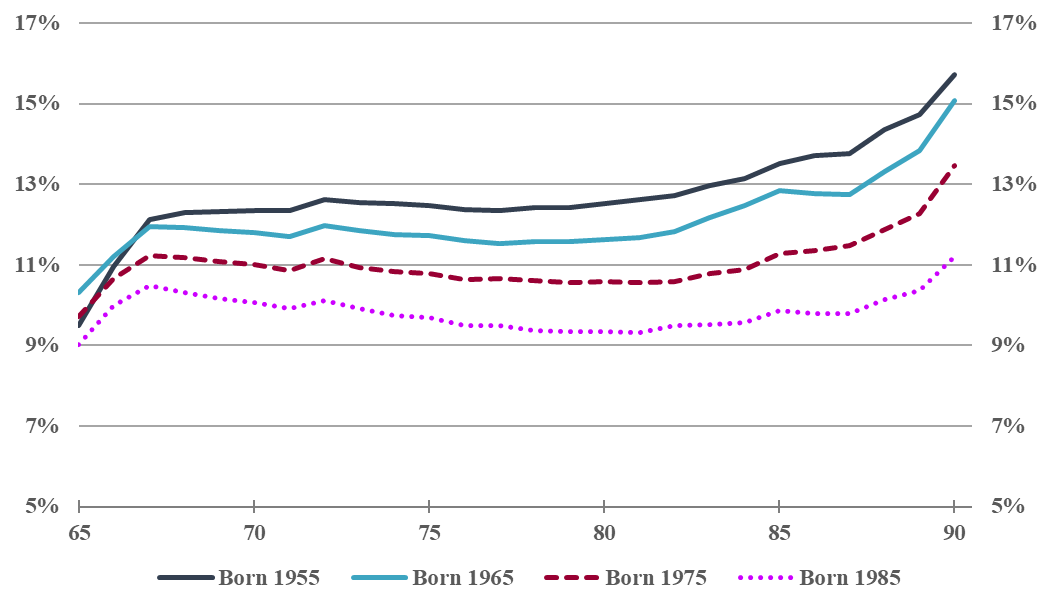

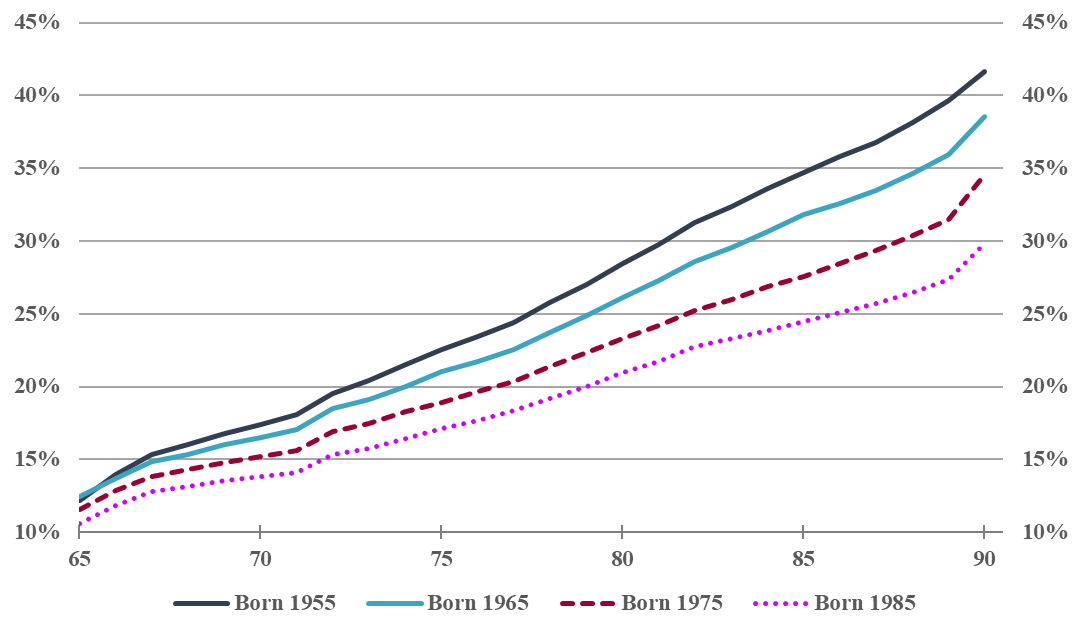

(amounts and % of total pensions payable) - Chart 13 GIS Single Recipient Rates (Males)

- Chart 14 GIS Single Recipient Rates (Females)

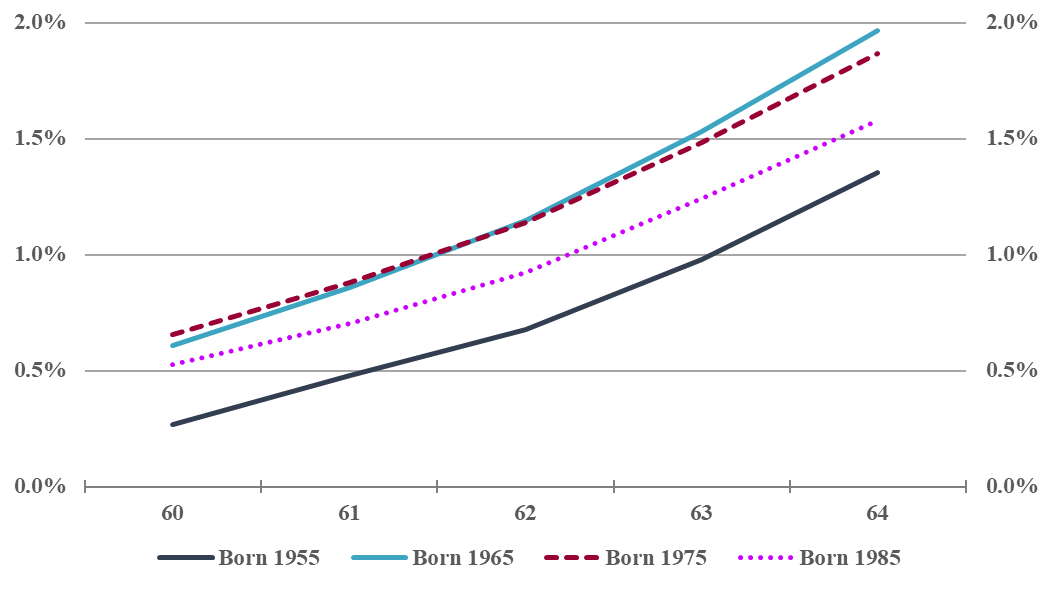

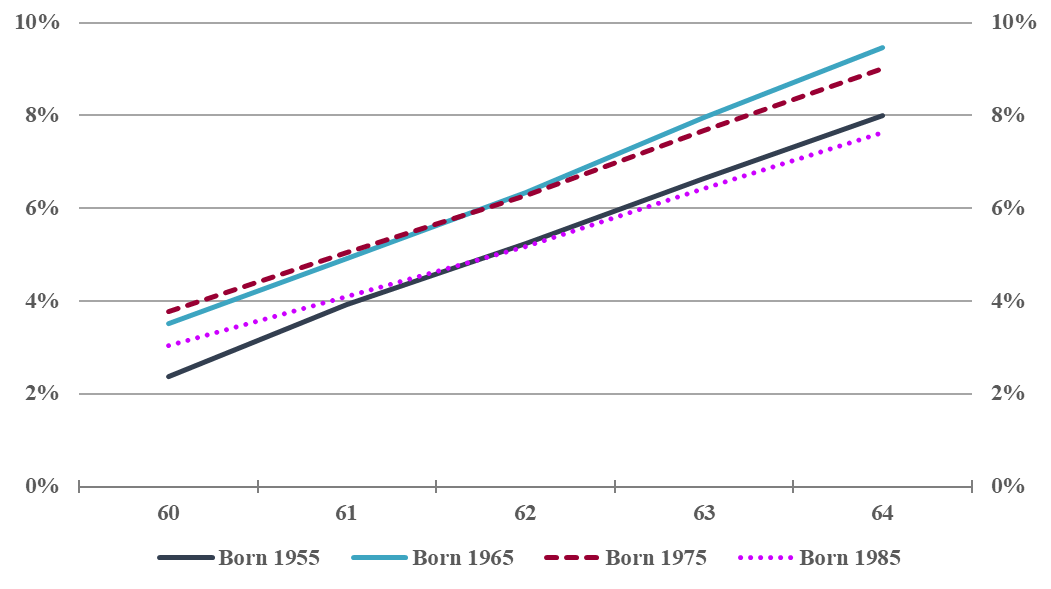

- Chart 15 Allowance Recipient Rates (Males)

- Chart 16 Allowance Recipient Rates (Females)

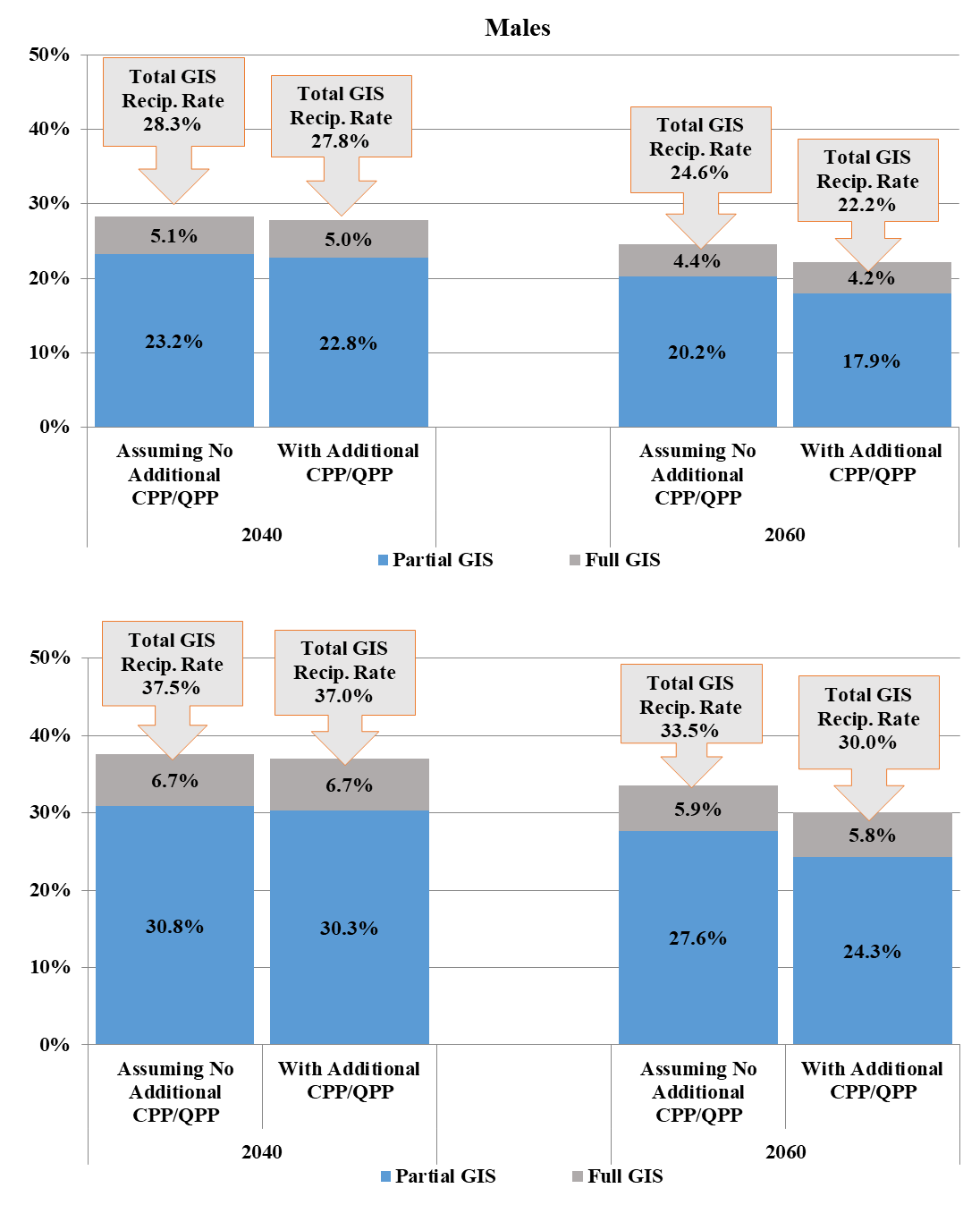

- Chart 17 Impact of Additional CPP and QPP on GIS Recipient Rates by Level of Benefit

1. Executive Summary

This is the 16th Actuarial Report on the Old Age Security program since the implementation of the Old Age Security Act in 1952. It presents the results of an actuarial review of the Old Age Security (OAS) program as at 31 December 2018, and includes projections of future experience through the year 2060. The previous triennial report is the 14th Actuarial Report on the Old Age Security program as at 31 December 2015, which was tabled in the House of Commons on 16 August 2017. The next triennial report is scheduled as at 31 December 2021.

This 16th OAS Actuarial Report takes into account three subsequent eventsFootnote 1, that is, events that became known to the Chief Actuary after the valuation date, but before the report date, that were deemed to have an effect on the actuarial review of the OAS program as at the valuation date. They are:

- The amendments to the OAS program under Bill C-97 – Budget Implementation Act, 2019, No. 1, which received Royal Assent on 21 June 2019 (effective 1 July 2020, increase the income exemption for GIS and Allowance benefits). These amendments were covered in the 15th Actuarial Report Supplementing the Actuarial Report on the Old Age Security program as at 31 December 2015, which was tabled in the House of Commons on 21 August 2019.

- The use of updated population estimates (for years 2018 and prior) from Statistics Canada that became available in January 2019.

- The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economic assumptions used in this report. It is important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic is a very fluid situation that will likely continue to evolve for some time. We have estimated the impacts based on the information known at the time the report was prepared. The final impacts of this health and economic crisis will likely generate some differences in the future.

The introduction of additional benefits under the Québec Pension Plan (QPP) (commencing 1 January 2019) have been taken into account. As such, the estimates presented in this report now take account of both the additional Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and the additional QPP.

1.1. Purpose of Report

This report has been prepared in compliance with the timing and information requirements of the Public Pensions Reporting Act, which provides that the Chief Actuary shall prepare a triennial actuarial report on the benefits under the various Parts of the Old Age Security Act, being as follows:

- Part I: OAS Basic Pension

- Part II: Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS)

- Part III: Allowance

Another important purpose of the report is to inform the general public of the current and projected costs of the OAS program. The report provides information to evaluate the program's financial situation over a long period, provided the program remains unchanged. Such information should facilitate a better understanding of the program and the factors that influence its costs, and thus contribute to an informed public discussion of issues related to it.

1.2. Scope of Report

Section 2 presents a general overview of the methodology used in preparing the actuarial estimates included in this report, which are based on the best-estimate assumptions described in section 3. The results are presented in section 4 and include information on key demographic and financial indicators and on the projection of beneficiaries, expenditures, and cost ratios. Section 5 presents the reconciliation of the results with those presented in the previous triennial (14th) report. Section 6 presents a general conclusion, and section 7 provides the actuarial opinion.

The various appendices provide supplemental information on the uncertainty of results based on sensitivity analysis of the key best-estimate assumptions, the program provisions, detailed reconciliations of the results between the 14th Actuarial Report on the OAS program and this report, a description of the data, assumptions and methodology used in this report, detailed projections of beneficiaries and expenditures, and lastly acknowledgements.

1.3. Main Findings

The key observations and findings of this report are:

- Demographic changes, notably the aging of the Canadian population, will have a major impact on the ratio of the number of people aged 20 to 64 to those aged 65 and over. This ratio is projected to fall from about 3.3 in 2020 to 2.0 in 2060.

- The number of beneficiaries of the OAS basic pension is projected to increase by 53% over the period 2020 to 2035, growing from 6.6 million in 2020 to 10.1 million by 2035, mainly due to the retirement of the baby boom generation reaching age 65 over that period. Thereafter, the growth in the number of beneficiaries is projected to slow down. By 2060, the number of OAS basic pension beneficiaries is projected to reach 12.7 million.

- OAS basic pension annual expenditures are projected to increase from $46.3 billion in 2020 to $94.3 billion in 2035 and $195.5 billion by 2060.

- The number of GIS and Allowance beneficiaries is projected to increase by 52% over the period 2020 to 2035, growing from 2.3 million in 2020 to 3.5 million by 2035. The GIS recipient rate (i.e. the proportion of the Canadian population that has received, receives, or is projected to receive the GIS) is projected to increase from its current level of 32.3% in 2020 to 33.1% by 2035 and to then slowly decrease to 26.3% by 2060.

- GIS and Allowance annual expenditures are projected to increase from $14.3 billion in 2020 to $28.6 billion in 2035 and $46.9 billion by 2060.

- The introduction of the additional CPP and QPP will affect the GIS and Allowance recipient rates and the amount of expenditures. The impact of the additional CPP and QPP will be very gradual and, by 2060, results in projected overall reductions of 390,000 (or -10.2%) in the number of GIS beneficiaries and of $4.8 billion (or -9.6%) in annual GIS expenditures.

- Total annual OAS program expenditures are projected to increase from $60.8 billion in 2020 to $123.4 billion in 2035 and $243.4 billion by 2060.

- The ratio of program expenditures to the GDP is projected to be 2.77% in 2020 compared to 2.50% in 2019. This substantial year-over-year increase is mainly due to the estimated negative impact of COVID-19 on the GDP. Thereafter, this ratio is projected to reach a high of 3.1% between 2030 and 2037. After 2037, the ratio of expenditures to GDP is projected to gradually decrease to a level of 2.63% by 2060 which is comparable to the historical levels of the early 1990s. This reduction is mainly attributable to expected slower growth in inflation compared to growth in wages and GDP and to increases in additional CPP and QPP benefits.

1.4. Uncertainty of Results

To measure the sensitivity of the long-term projections of the program to future changes in the demographic and economic environments, different sensitivity tests were performed. The tests and results are presented in detail in Appendix A of this report.

The tests focus on varying the key best-estimate assumptions individually in order to measure the potential impact on the cost ratio of program expenditures to GDP. These tests show that the cost ratios could deviate significantly from their projected best‑estimate values if other than best-estimate assumptions were to be realized. For example, if life expectancies at age 65 were to increase by about two more years than the best estimates of this report, then the ratio in 2060 would increase from 2.63% to 2.80%. As another example, if benefit rates were increased to partially reflect the growth in real wages, then the ratio in 2060 would increase from 2.63% to 3.42%.

Scenario tests were also performed regarding the future economic growth and aging of the population, and how they may differ from the best-estimate projection. Two alternative economic scenarios were developed that portray higher and lower economic growth, and two demographically based scenarios were developed that portray generally younger and older populations. The economic scenarios produced cost ratios of program expenditures to GPD in 2060 of 1.85% (higher economic growth) and 3.78% (lower economic growth), while the demographic scenarios produced cost ratios of program expenditures to the GDP in 2060 of 2.40% (younger population) and 2.80% (older population).

1.5. Conclusion

The ratio of program expenditures to the GDP is projected to be 2.77% in 2020 compared to 2.50% in 2019. This substantial year-over-year increase is mainly due to the estimated negative impact of COVID-19 on the GDP. The retirement of the baby boomers reaching age 65 over the next few decades is projected to increase the expenditures of the program and the ratio is projected to reach a high of 3.1% between 2030 and 2037. Thereafter, although the impacts of Tax Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs) reduce the amount of income for benefit calculation purposes and tend to increase this ratio over the long term, the projected gradual growth in additional CPP and QPP benefits and the fact that OAS benefits are indexed to inflation as opposed to wages drive down the cost of the OAS program relative to the GDP over the long term. As a result, annual expenditures are expected to gradually fall to 2.63% of GDP by 2060 which is comparable to the historical levels of the early 1990s.

In comparison with the previous triennial (14th) Actuarial Report on the OAS program, the amendments which increase, effective 1 July 2020, the GIS and Allowance income exemption, slightly increase the projected expenditures by 0.01% of GDP by 2030. Changes in the economic assumptions (especially lower real wage growth) also lead to increases in the cost ratio. These increases are offset by the update in experience and changes to demographic and benefit assumptions. The net result is lower expenditures relative to the GDP over the projection period as compared to the previous 14th Actuarial Report on the OAS program.

2. Methodology

The actuarial examination of the OAS program involves projections of its expenditures and cost measurement bases over a long period of time, so that the future impact of historical and projected trends in demographic and economic factors can be properly assessed. The actuarial estimates in this report are based on the provisions of the Old Age Security Act as at 31 December 2018Footnote 2, data regarding the starting point for the projections, and best‑estimate assumptions regarding future demographic and economic experience.

Since the OAS program is financed from general tax revenues on a pay‑as‑you‑go basis, there is no need to project either contributions or investment earnings. However, projected total employment earnings and GDP levels are used as bases for measuring the relative costs over the projection period.

The costing begins with a projection of the general population of Canada. This requires assumptions regarding demographic factors such as fertility, migration, and mortality.

Expenditures are made up of the benefits paid out and administrative expenses. Benefits are projected by applying assumptions regarding recipient rates for various types and levels of benefits to the projected population at the relevant ages, along with assumptions regarding increases in the maximum benefit rates. Administrative expenses are projected by considering the historical relationship between expenses and total benefit expenditures.

The total employment earnings cost measurement basis is derived by applying labour force participation and job creation rates to the projected population and by projecting future employment earnings. This requires assumptions about various factors such as wage increases, an earnings distribution and unemployment rates. The GDP is projected based on the historical relationship between the GDP and total employment earnings.

The assumptions and results presented in the following sections make it possible to measure the costs of the OAS program over the projection period. A wide variety of factors influence both the current and projected costs of the program. Accordingly, the results shown in this report differ from those shown in previous reports. Likewise, future actuarial examinations will reveal results that differ from the projections included in this report.

3. Best-Estimate Assumptions

3.1. Introduction

The information required by statute, which is presented in section 4 of this report, requires making several assumptions regarding future demographic and economic trends. The projections included in this report cover a long period of time (up to the year 2060) and the assumptions are determined by examining historical long-term and short-term trends, and by applying judgement as to the extent these trends will continue in the future. These assumptions reflect the Chief Actuary's best judgment and are referred to in this report as the best-estimate assumptions. The assumptions were chosen to be, independently reasonable and appropriate in the aggregate, taking into account certain interrelationships between them. To the extent applicable, and with the exception of certain adjustments resulting from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the assumptions are consistent with the best-estimate assumptions used in the 30th Actuarial Report on the Canada Pension Plan as at 31 December 2018.

This actuarial report on the Old Age Security program presents projections of its expenditures over a long period of time. Both the length of the projection period and the number of assumptions required ensure that actual future experience will not develop precisely in accordance with the best-estimate projections. To measure the sensitivity of the long-term projections to future changes in demographic and economic environments, a variety of sensitivity tests were performed. The tests and results are presented in Appendix A of this report.

The assumptions were developed taking into account three subsequent eventsFootnote 3, that is, events that became known to the Chief Actuary after the valuation date, but before the report date, that were deemed to have an effect on the actuarial review of the OAS program as at the valuation date. They are:

- The amendments to the OAS program under Bill C-97 – Budget Implementation Act, 2019, No. 1, which received Royal Assent on 21 June 2019 (effective 1 July 2020, increase the income exemption for GIS and Allowance benefits). These amendments were covered in the 15th Actuarial Report Supplementing the Actuarial Report on the Old Age Security program as at 31 December 2015, which was tabled in the House of Commons on 21 August 2019.

- The use of updated population estimates (for years 2018 and prior) from Statistics Canada that became available in January 2019.

- The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economic assumptions used in this report. It is important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic is a very fluid situation that will likely continue to evolve for some time. We have estimated the impacts based on the information known at the time the report was prepared. The final impacts of this health and economic crisis will likely generate some differences in the future.

The introduction of additional benefits under the Québec Pension Plan (QPP) (commencing 1 January 2019) have also been taken into account. As such, the estimates presented in this report now take account of both the additional Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and the additional QPP.

Table 1 presents a summary of the most important assumptions used in this report compared with those used in the previous (14th) triennial report. The assumptions are described in more detail in Appendix D of this report.

| Canada | 16th Report (as at 31 December 2018) |

14th Report (as at 31 December 2015) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Fertility Rate | 1.62 (2027+) | 1.65 (2019+) | ||||||

| Mortality | Statistics Canada Life Table (CLT 3-year average table: 2014 – 2016) with assumed future improvements |

Canadian Human Mortality Database (CHMD 2011) with assumed future improvements |

||||||

| Canadian Life Expectancy | Males | Females | Males | Females | ||||

| at birth in 2019 | 86.9 years | 89.9 years | 87.0 years | 89.9 years | ||||

| at age 65 in 2019 | 21.4 years | 23.9 years | 21.5 years | 23.9 years | ||||

| Net Migration Rate | 0.62% of population (for 2021+) | 0.62% of population (for 2016+) | ||||||

| Participation Rate (age group 18-69) | 79.2% | (2035) | 79.1%Table 1 - Footnote 2 | (2035) | ||||

| Employment Rate (age group 18-69) | 74.4% | (2035) | 74.4%Table 1 - Footnote 2 | (2035) | ||||

| Unemployment Rate (ages 15+) | 6.2% | (2030+) | 6.2% | (2025+) | ||||

| Rate of Increase in Prices | 2.0% | (2021+) | 2.0% | (2017+) | ||||

| Real Wage Increase | 1.0% | (2025+) | 1.1% | (2025+) | ||||

| 2019 | 2030 | 2060 | 2019 | 2030 | 2060 | |||

| Recipient ratesTable 1 - Footnote 1 | OAS: | 96.3% | 97.0% | 97.5% | OAS: | 96.1% | 96.7% | 97.2% |

| GIS: | 31.1% | 33.4% | 26.3% | GIS: | 30.7% | 31.2% | 25.3% | |

| Allowance: | 2.8% | 4.3% | 3.1% | Allowance: | 2.8% | 3.2% | 2.6% | |

|

||||||||

3.2. Demographic Assumptions

The population projections start with the population of Canada on 1 July 2018, to which are applied fertility, migration, and mortality assumptions. The population projections are essential to determine the future number of OAS program beneficiaries. The distribution of the population by age changed considerably with the arrival of the baby boom generation, and the population has been aging since. The causes of this aging are examined in the following subsections.

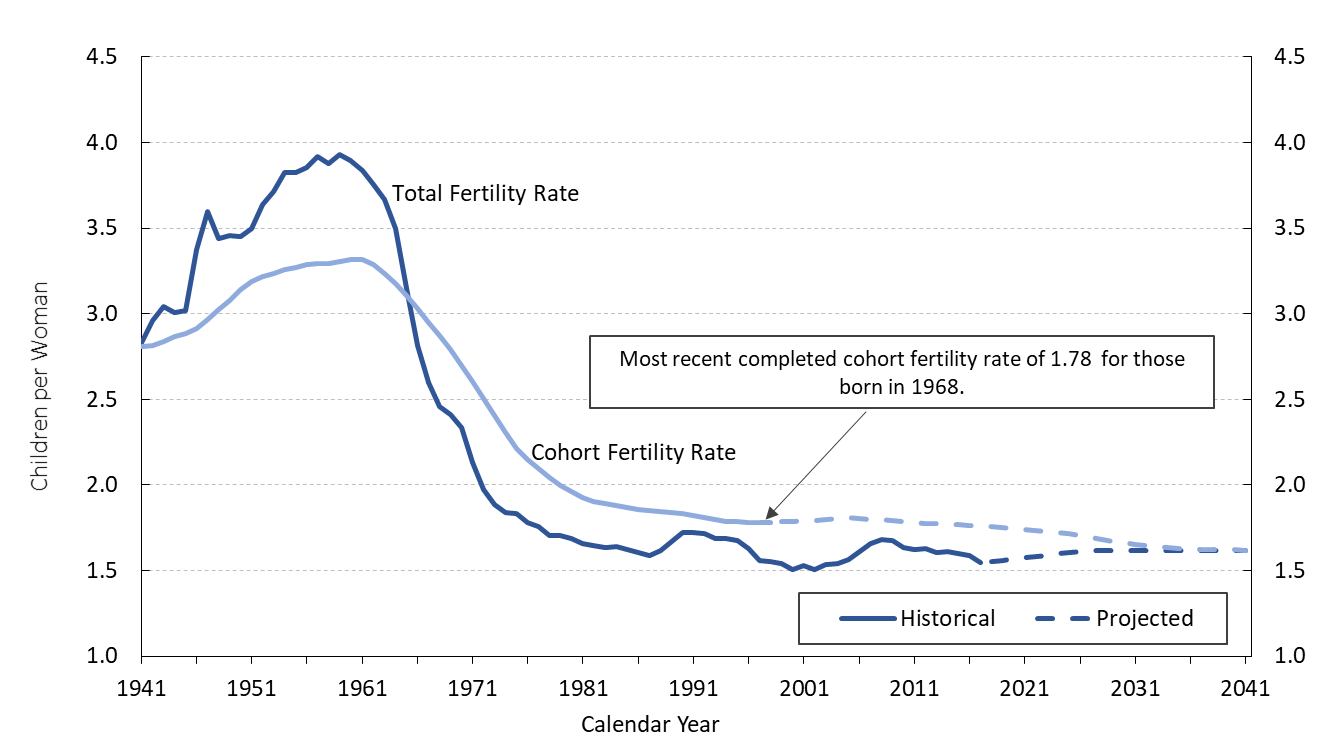

3.2.1. Fertility

The first cause of the aging of the Canadian population is the decline in the total fertility rate that occurred during the last 50 years. The total fertility rate in Canada decreased rapidly from a level of about 4.0 children per woman in the late 1950s to 1.6 by the mid-1980s. The total fertility rate rose slightly in the early 1990s, but then declined to a level of 1.5 by the late 1990s. Canada is one of many industrialized countries that saw their fertility rates increase starting in the 2000s. By 2008, the total fertility rate for Canada reached 1.68. However, in some industrialized countries, including Canada, the total fertility rate has decreased since 2008, which could be attributable to the most recent economic downturn experienced. As of 2017, the total fertility rate for Canada stood at 1.55Footnote 4.

The overall decrease in the total fertility rate since the 1950s occurred as a result of changes in a variety of social, medical, and economic factors. Although there have been periods of growth in the total fertility rates in recent decades, it is unlikely that the rates will return to historical levels in the absence of significant societal changes. The assumed age-specific fertility rates lead to an assumed total fertility rate for Canada that will increase from its 2017 level of 1.55 children per woman to an ultimate level of 1.62 in 2027.

3.2.2. Mortality

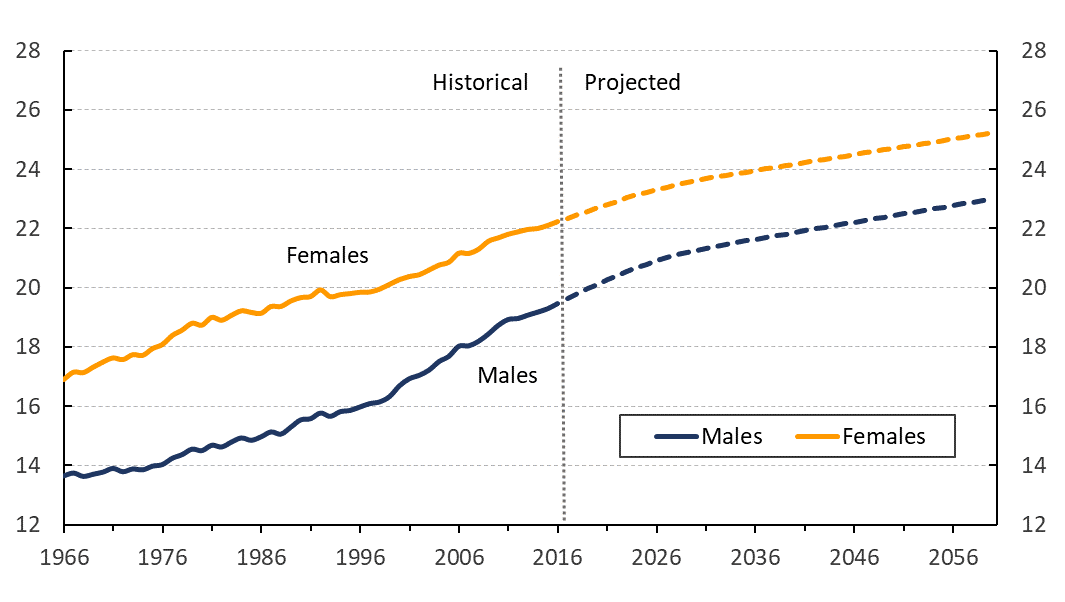

Another element that has contributed to the aging of the population is the significant reduction in the age-specific mortality rates. This can be measured by the increase in life expectancy at age 65, which directly affects how long retirement benefits will be paid to beneficiaries. Male life expectancy (without future mortality improvements, i.e. reductions in mortality) at age 65 increased by 42% between 1966 and 2015, rising from 13.6 to 19.3 years. For women, life expectancy at age 65 (without future improvements) increased by 31%, from 16.9 to 22.1 years over the same period. Although the overall gains in life expectancy at age 65 since 1966 are similar for males and females (between 5 and 6 years), about 65% of the increase occurred after 1991 for males, while for females, only about 45% of the increase occurred in that period.

Mortality improvements are expected to continue in the future, but at a slower pace than most recently observed over the 15-year period ending in 2015. Further, it is assumed that ultimately, mortality improvement rates for males will decrease to the same level as for females. The analysis of the Canadian experience over the period 1925 to 2015, including the recent slowdown trends observed in mortality improvement rates for OAS beneficiariesFootnote 5, was combined with an analysis of the possible drivers of future mortality improvements.

The 15-year average mortality improvement rates by age and sex for the period ending in 2015 are the starting point for the projected annual mortality improvement rates from 2016 onward. For ages 65 and over, the annual mortality improvement rates for 2016 to 2017 were estimated using the trends derived from the administrative data on OAS beneficiaries, representing 98% of the general population.

Starting from 2015 (2017 for ages 65 and over), the rates are assumed to gradually reduce to their ultimate levels in 2035, which are for both sexes 0.8% per year for ages below 90, 0.5% for ages 90 to 94, and 0.2% for ages 95 and above. Considering future mortality improvements, life expectancy at age 65 in 2019 is projected to be 21.4 years for males, and 23.9 years for females. This represents a decrease of 0.1 years in life expectancy at age 65 in 2019 for males and no change for females, relative to the 14th OAS Actuarial Report projections.

3.2.3. Net Migration

Net migration corresponds to the number of immigrants less the number of emigrants, plus the number of returning Canadians and the net increase in the number of non-permanent residents.

The net migration rate is expected to decrease from its current (2018) level of 1.11% of the population to 0.86% in 2019, 0.73% in 2020, and reach an ultimate level of 0.62% of the population for the year 2021 and thereafter. The ultimate net migration rate of 0.62% corresponds to the average experience observed over the last 10 years, excluding the net increase in non-permanent residents during that period.

3.2.4. Population Projections

Table 2 shows the population of Canada for three age groups (0-19, 20-64 and 65 and over) throughout the projection period. The ratio of the number of people aged 20-64 to those aged 65 and over is a measure that approximates the ratio of the number of working-age people to retirees. Because of the aging population, this ratio is projected to drop from 3.3 in 2020 to 2.0 in 2060.

The number of people reaching age 65 in any given year is a good indicator of the number of new basic pension beneficiaries coming into pay each year. This population is expected to increase from 475,000 in 2020 to 523,000 by 2030.

| Year | Total | Age 0-19 | Age 20-64 | Age 65 and Over |

Ratio of 20‑64 to 65 and Over |

Reaching Age 65 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 37,499 | 8,115 | 22,780 | 6,604 | 3.4 | 457 |

| 2020 | 37,899 | 8,144 | 22,892 | 6,862 | 3.3 | 475 |

| 2021 | 38,259 | 8,175 | 22,961 | 7,122 | 3.2 | 482 |

| 2022 | 38,621 | 8,226 | 23,005 | 7,390 | 3.1 | 496 |

| 2023 | 38,986 | 8,292 | 23,031 | 7,663 | 3.0 | 507 |

| 2024 | 39,351 | 8,361 | 23,054 | 7,937 | 2.9 | 513 |

| 2025 | 39,717 | 8,437 | 23,065 | 8,215 | 2.8 | 525 |

| 2030 | 41,502 | 8,726 | 23,248 | 9,528 | 2.4 | 523 |

| 2035 | 43,108 | 8,957 | 23,828 | 10,323 | 2.3 | 475 |

| 2040 | 44,512 | 9,157 | 24,520 | 10,836 | 2.3 | 471 |

| 2045 | 45,769 | 9,265 | 25,258 | 11,245 | 2.2 | 511 |

| 2050 | 46,948 | 9,357 | 25,864 | 11,727 | 2.2 | 554 |

| 2055 | 48,124 | 9,534 | 26,308 | 12,282 | 2.1 | 604 |

| 2060 | 49,362 | 9,790 | 26,585 | 12,988 | 2.0 | 623 |

3.3. Economic Assumptions

The OAS program expenditures are presented as cost ratios using two different measurement bases, namely total employment earnings and the GDP. These cost bases are projected using economic assumptions for indicators such as labour force participation rates, job creation rates, unemployment rates, and nominal increases in average employment earnings. For benefit projection purposes, assumptions regarding the rate of increase in prices and recipient rates for the various benefits are also required.

All economic assumptions are consistent with the 30th CPP Actuarial Report, except that we have adjusted some of the economic assumptions to reflect the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The details of these adjustments appear in section 4 of Appendix D. It is important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic is a very fluid situation that will likely continue to evolve for some time. We have estimated the impacts based on the information known at the time the report was prepared. The final impacts of this health and economic crisis will likely generate some differences in the future.

One of the key elements underlying the best estimate economic assumptions relates to the continued trend toward longer working lives. Older workers are expected to exit the workforce at a later age, which could alleviate the impact of the aging of the population on future labour force growth. However, despite the expected later exit ages, labour force growth is projected to weaken as the working-age population expands at a slower pace and baby boomers exit the labour force. As a result, labour shortages together with projected improvements in productivity growth are assumed to create upward pressure on real wages until 2025.

3.3.1. Labour Force

Employment levels vary with the rate of unemployment, and reflect trends in increased workforce participation by women, longer periods of formal education among young adults, as well as changing retirement patterns of older workers.

As the population ages, older age groups with lower labour force participation increase in size. As a result, the labour force participation rate for Canadians aged 15 and over is expected to decline from 65.2% in 2019 to 63.0% in 2035. A more useful measure of the working-age population is the participation rate of those aged 18 to 69, which is expected to increase from 76.0% in 2019 to 79.2% in 2035.

The increase in the participation rate for those aged 18 to 69 is mainly due to an assumed increase in participation rates for those aged 55 and over as a result of an expected continued trend toward longer working lives. Furthermore, labour shortages create attractive employment opportunities that will continue to exert upward pressure on the participation rates for all age groups. It is also expected that future participation rates will increase with the aging of cohorts that have a stronger labour force attachment compared to previous cohorts due to higher education attainment. The cohort effect of stronger labour force attachment of women is expected to continue but at a much slower pace than in the past, resulting in a gradual narrowing of the gap between the age-specific participation rates of men and women.

As a result, the participation rates for females are projected to increase slightly more than for males. Overall, the male participation rate of those aged 18 to 69 is expected to increase from 79.8% in 2019 to 82.8% in 2035, while the female participation rate for the same age group is expected to increase from 72.1% in 2019 to 75.6% in 2035. Thereafter, the 2035 gap of 7.2% between males and females in this age group is expected to vary between 7.0% and 7.2%.

The job creation rate (i.e. the change in the number of persons employed) in Canada was on average 1.6% from 1976 to 2018 based on available employment data, and it is assumed that the rate will be 1.1% in 2019. The job creation rate assumption is determined on the basis of expected moderate economic growth. However, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the unemployment rate is assumed to increase significantly in 2020, and then to revert to its pre-pandemic projected level by 2024 before reaching its ultimate level in 2030. The unemployment rate for Canada, ages 15 and over, is expected to increase from 5.8% in 2018 to 5.9% in 2019, and to 10.5% in 2020. It is then expected to decrease to 6.0% by 2024, before gradually increasing to an ultimate level of 6.2% by 2030. In 2020, the assumed job creation rate for Canada, ages 15 and over, is expected to be -4.1%, compared to an annual average of 1.9% from 2021 to 2024 and 0.6% from 2025 to 2030. It is assumed that, starting in 2030, the job creation rate will follow the labour force growth rate, with both averaging 0.7% per year between 2030 and 2035, and 0.5% per year thereafter. The aging of the population is the main reason behind the expected slower long-term growth in the labour force and job creation rate.

3.3.2. Price Increases

Price increases, as measured by changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), tend to fluctuate from year to year. In Canada, increases in prices (inflation) was 2.3% in 2018.

In 2016, the Bank of Canada and the Government renewed their commitment to keep inflation between 1% and 3% until the end of 2021. The Senior Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada indicated in November 2018 that the Bank was undergoing an extensive review of its monetary policy framework. A number of variants to replace the inflation target are being explored. The Bank is also looking at a possible dual mandate of targeting inflation as well as GDP growth or employmentFootnote 6. Nevertheless, given the success of the 2% inflation target, it is considered very likely that the Bank will renew its inflation target commitment or that the target will at least constitute an important part of the Bank's future mandate.

Price increase forecasts from various economists indicate an average increase in prices of 2.0% from 2019 to 2040. To reflect these forecasts and the expectation that the Bank of Canada will renew its inflation target, the price increase assumption is set at 2.0% for 2019, 1.0% in 2020 (to reflect the impact of COVID-19) and at 2.0% thereafter.

3.3.3. Real Wage Increases

Wage increases affect the financial balance of the OAS program in two ways. In the short term, an increase in the average wage translates into higher total employment earnings and GDP, with little immediate impact on benefits. Therefore, costs in relation to these measurement bases will decrease. Over the longer term, higher average wages in relation to the level of prices could be expected to produce lower payouts for income-tested benefits such as the GIS and Allowance.

The difference between nominal wage increases and inflation represents increases in the real wage, which is also referred to in this report as the real wage increase. There are five main factors that influence increases in the real wage, namely general productivity, the extent to which changes in productivity are shared between labour and capital, changes in the compensation structure offered to employees, changes in the average number of hours worked, and changes in labour's terms of tradeFootnote 7.

The real wage increase is projected to gradually rise from 0.3% in 2019 to an ultimate value of 1.0% by 2025. The ultimate real wage increase assumption is developed taking into account the relationships described above, historical trends, labour shortages, and other changes in the labour market. The ultimate real wage increase assumption combined with the ultimate price increase assumption results in an assumed annual increase in average nominal wages of 3.0% in 2025 and thereafter.

The assumptions regarding the increase in average real annual employment earnings and job creation rates result in projected average annual real increases in total Canadian employment earnings of about 1.6% for the period 2018 to 2035. After 2035, this decreases to about 1.5% on average over the remainder of the projection period, reflecting the assumed 1.0% real increase in annual wages and projected average 0.5% annual growth in the working age population.

Given historical trends and the long-term relationship between increases in the average annual employment earnings and the YMPE, it is assumed that the nominal wage increase assumption is also applicable to the increases in the YMPE from one year to the next. Table 3 summarizes the main economic assumptions over the projection period.

| Year | Real Increase Average Annual Earnings |

Real Increase Average Weekly Earnings |

Price Increase |

Labour Force (Canada) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation Rate (Ages 15+) |

Job Creation Rate |

Unemployment Rate |

Labour Force Annual Increase |

||||

| 2019 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 65.2 | 1.1 | 5.9 | 1.1 |

| 2020 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 65.1 | (4.1) | 10.5 | 0.8 |

| 2021 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 64.9 | 3.5 | 8.0 | 0.7 |

| 2022 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 64.7 | 1.8 | 7.0 | 0.7 |

| 2023 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 64.5 | 1.2 | 6.5 | 0.7 |

| 2024 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 64.3 | 1.2 | 6.0 | 0.7 |

| 2025 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 64.1 | 0.6 | 6.1 | 0.7 |

| 2030 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 63.2 | 0.6 | 6.2 | 0.6 |

| 2035 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 63.0 | 0.7 | 6.2 | 0.7 |

| 2040 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 62.5 | 0.6 | 6.2 | 0.6 |

| 2045 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 62.2 | 0.5 | 6.2 | 0.5 |

| 2050 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 61.9 | 0.4 | 6.2 | 0.4 |

| 2055 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 61.5 | 0.3 | 6.2 | 0.3 |

| 2060 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 61.0 | 0.3 | 6.2 | 0.3 |

3.3.4. Recipient Rates

OAS recipient rates represent the proportion of the Canadian population that has received (historically), receives, or is projected to receive OAS program benefits. Recipient rates are different than coverage or eligibility rates for benefits, which are higher, since individuals upon becoming eligible for benefits don't necessarily apply for them immediately, but may rather defer application and commencement of their benefits (for reasons such as to receive actuarially-adjusted higher benefits for voluntary deferrals or to increase benefits from partial to full amounts by accruing more years of residence).

The recipient rate for a given benefit is derived as the ratio of the number of beneficiaries receiving that benefit to the population. It is worth noting that recipient rates for the OAS basic pension presented in this report exclude the impact of the OAS Recovery Tax. The impact of the OAS Recovery Tax on the basic pension recipient rates is discussed in section 5 of Appendix D of this report.

As shown in Table 4, the overall basic pension recipient rate for males is projected to increase from 95.5% in 2019 to 97.0% in 2060, while for females it is projected to increase from 97.1% to 98.0% over the same period. The rates for both sexes increase over time primarily due to the aging of the population. Moreover, the basic pension recipient rates include benefits paid outside of Canada and as such, could exceed 100%.

The GIS and Allowance recipient rates by age, sex, type and level of benefit for year 2019 were used as the starting point for determining the corresponding best-estimate assumptions. These rates were further adjusted for years 2020 and thereafter to account for the new income exemption that will come into effect on 1 July 2020.

GIS and Allowance recipient rates are projected under the assumption that initial retirement income increases in line with the rate of wage growth, where such retirement income mainly comprises CPP and QPP benefits (including additional CPP and QPP benefits starting in 2019). At the same time, it is assumed that the income limits for the GIS and Allowance will have increased in line with inflation prior to retirement. Together, this would normally result in a lower proportion of new retirees becoming eligible for these benefits over the projection period. However, the effect of TFSA income being excluded for GIS and Allowance benefits is projected to partially offset the expected decline in recipient rates for these benefits. For this report, the impact of the additional CPP and QPP benefits on eligibility and level of benefit has also been reflected. Section 5 of Appendix D of this report discusses in more detail the effect of the additional CPP and QPP on GIS and Allowance benefits.

Furthermore, for the GIS and Allowance, experience adjustment factors are used to adjust the projected recipient rates so that characteristics and trends of historical recipient rates by age, sex, type and level of benefit over the period 2015 to 2019 would be reproduced more closely. These experience adjustment factors are used for the first five years of the projection period, so that there is a gradual change in the assumed recipient rates by level of benefit that reflects a transition from the historical experience to the longer term projections.

Table 4 presents a summary of the projected recipient rates by type of benefit.

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2030 | 2060 | 2019 | 2030 | 2060 | |

| OAS | 95.5 | 96.4 | 97.0 | 97.1 | 97.5 | 98.0 |

| GIS-Single | 11.8 | 12.8 | 10.6 | 24.2 | 24.9 | 21.6 |

| GIS-Spouse a Pensioner | 11.1 | 12.4 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 10.9 | 7.6 |

| GIS-Spouse not a Pensioner | 2.5 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| GIS-Spouse with Allowance | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| GIS-AllTable 4 - Footnote 3 | 26.9 | 29.4 | 22.2 | 34.6 | 36.9 | 30.0 |

| Allowance-Regular | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 6.0 | 4.9 |

| Allowance-Survivor | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| Allowance-AllTable 4 - Footnote 3 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 4.9 | 7.1 | 5.3 |

|

||||||

4. Results

4.1. Overview

The key observations and findings of this report are described below.

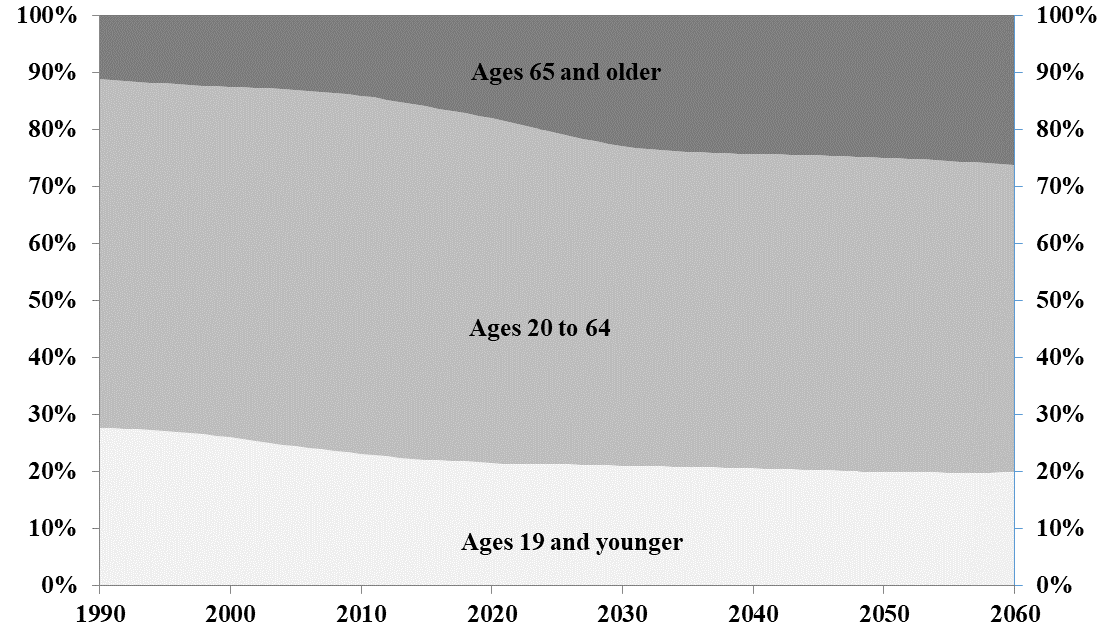

- Demographic changes, notably the aging of the Canadian population, will have a major impact on the ratio of the number of people aged 20 to 64 to those aged 65 and over. This ratio is projected to fall from about 3.3 in 2020 to 2.0 in 2060. Chart 1 shows an analysis of the Canadian population by age group.

- The number of beneficiaries of the OAS basic pension is projected to increase by 53% over the period 2020 to 2035, growing from 6.6 million in 2020 to 10.1 million by 2035, mainly due to the retirement of the baby boom generation reaching age 65 over that period. Thereafter, the growth in the number of beneficiaries is projected to slow down. By 2060, the number of OAS basic pension beneficiaries is projected to reach 12.7 million.

- OAS basic pension annual expenditures are projected to increase from $46.3 billion in 2020 to $94.3 billion in 2035 and $195.5 billion by 2060.

- The number of GIS and Allowance beneficiaries is projected to increase by 52% over the period 2020 to 2035, growing from 2.3 million in 2020 to 3.5 million by 2035. The GIS recipient rate (i.e. the proportion of the Canadian population that has received, receives, or is projected to receive the GIS) is projected to slowly increase from of 32.3% in 2020 to 33.1% in 2035 and to then slowly decrease to 26.3% by 2060.

- GIS and Allowance annual expenditures are projected to increase from $14.3 billion in 2020 to $28.6 billion in 2035 and $46.9 billion by 2060.

- The introduction of the additional CPP and QPP will reduce the GIS and Allowance recipient rates and the amount of expenditures. The impact of the additional CPP and QPP will be very gradual and, by 2060, together with other factors, lead to projected reductions of 390,000 (or -10.2%) in the number of GIS beneficiaries and of $4.8 billon (or -9.6%) in annual GIS expenditures.

- Total annual OAS program expenditures are projected to increase from $60.8 billion in 2020 to $123.4 billion in 2035 and $243.4 billion by 2060.

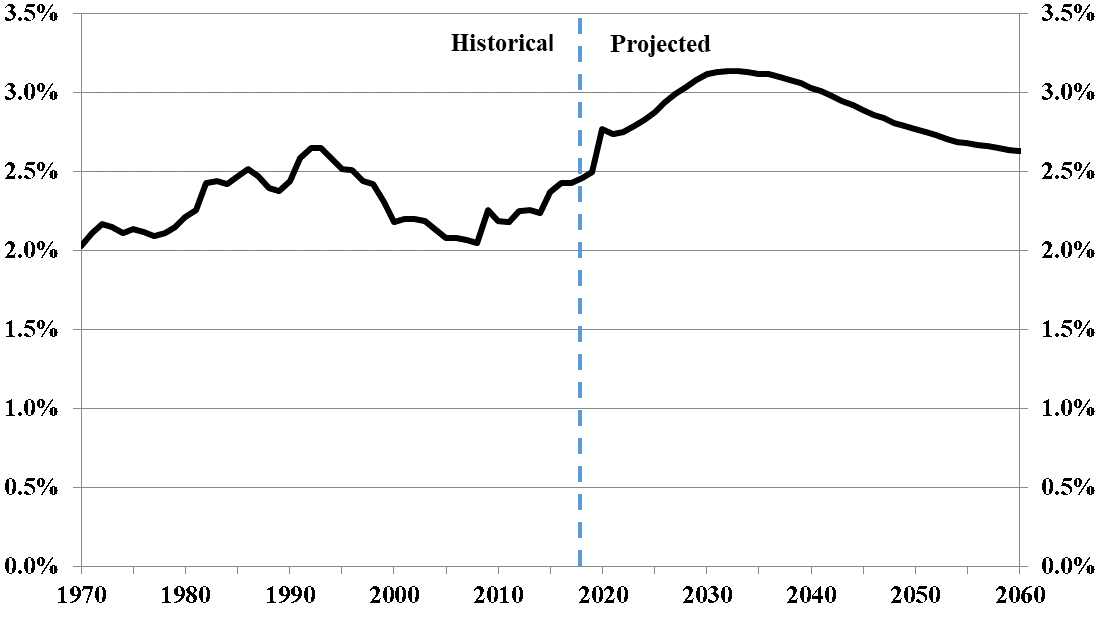

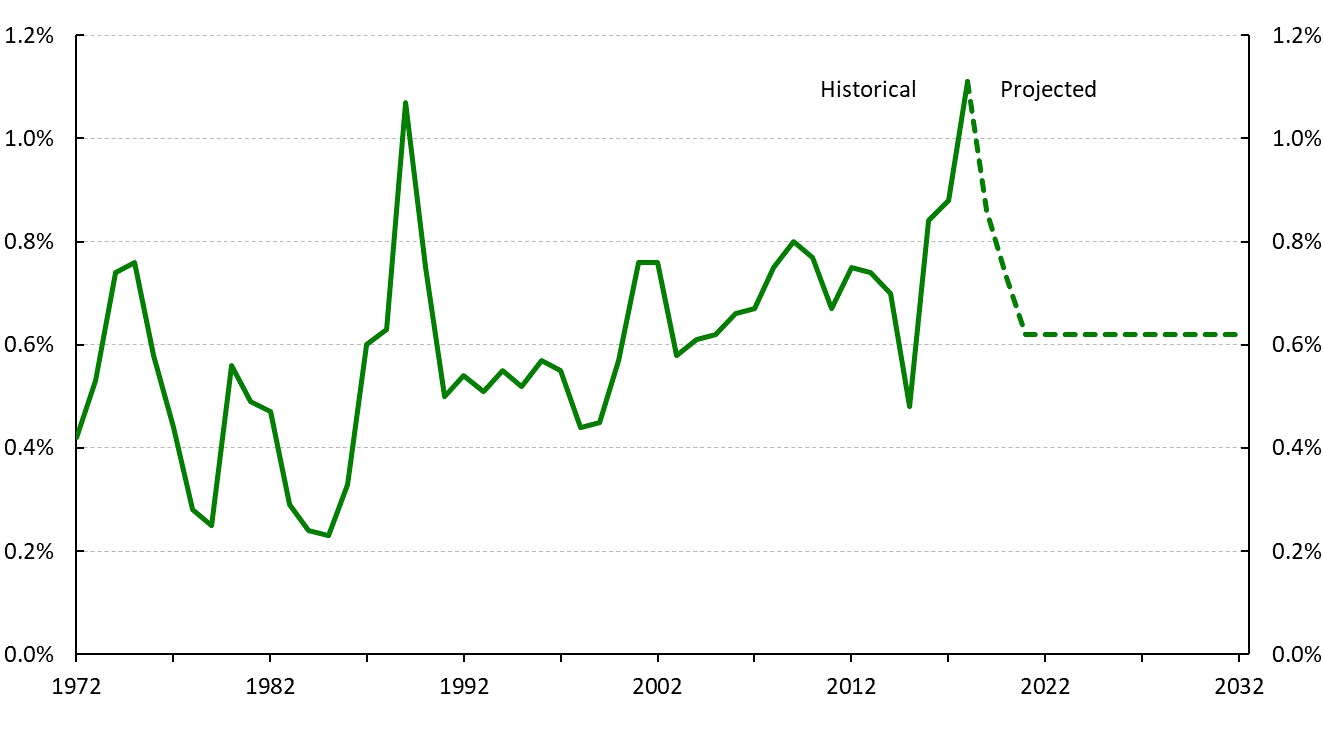

- The ratio of program expenditures to the GDP is projected to be 2.77% in 2020 compared to 2.50% in 2019. This substantial year-over-year increase is mainly due to the estimated negative impact of COVID-19 on the GDP. Thereafter, as shown in Chart 2, this ratio is projected to reach a high of 3.1% between 2030 and 2037. After 2037, the ratio of expenditures to GDP is projected to gradually decrease to a level of 2.63% by 2060 which is comparable to the historical levels of the early 1990s. This reduction is mainly attributable to expected slower growth in inflation compared to growth in wages and GDP and increases in additional CPP and QPP benefits.

Over time, price indexation of benefits that increases more slowly than the rate of growth in average employment earnings means that benefits will replace a decreasing share of an individual's pre-retirement earnings. In the past, this issue has been addressed through occasional ad hoc increases in the benefit rates. One of the sensitivity tests shown in Appendix A of this report provides an indication of the impact on projected results if benefit rates were increased to partially reflect the growth in real wages.

Chart 1 - Analysis of Population of Canada by Age Group

Chart 1 - Description

Stacked area chart showing the historical and projected distribution by age group of Canada's population. Y axis represents the percentage of the population. X axis represents the year.

The population aged 0 to 19 represents 28% of the total population in 1990, decreases to 22% by 2018, and is projected to further decrease to 20% by 2060.

The population aged 20 to 64 represents 61% of the total population in 1990 and in 2018, and is projected to decrease to 54% in 2060.

The population aged 65 and over represents 11% of the total population in 1990, increases to 17% in 2018, and is projected to increase to 26% in 2060.

Chart 2 - Expenditures as a Proportion of GDP

Chart 2 - Description

Line chart showing the historical and projected total OAS program expenditures as a percentage of GDP for Canada. Y axis represents the percentage of GDP. X axis represents the year.

Total OAS program expenditures are 2.03% of GDP in 1970, increase to reach 2.65% in 1992, then decrease to 2.05% in 2008, and increase again to 2.46% in 2018. After 2018, the proportion is projected to increase to 3.14% in 2032, and then decrease to 2.63% in 2060.

4.2. Number of Beneficiaries

Table 5 and Table 6 present the historical and projected number of beneficiaries along with the respective overall recipient rates. The number of beneficiaries is the product of the population and the relevant recipient rates, which vary by year, age, sex, and type and level of benefit. Beneficiaries include those who receive benefits outside of Canada. In 2018, about 1.4% of the population aged 65 and older was receiving a basic pension outside of Canada under international social security agreements.

The recipient rates shown in Table 6 reflect the eligible ages for program benefits, that is age 65 and over for the OAS basic pension and GIS, and ages 60 to 64 for the Allowance benefit. The OAS recipient rates also account for voluntary deferrals, which became effective 1 July 2013. The OAS basic pension recipient rates and number of beneficiaries shown in Table 5 and Table 6 are on a gross basis; that is, they have not been adjusted to account for the application of the OAS Recovery Tax, which is a provision of the Income Tax Act.

The OAS Recovery Tax, which applies to high-income pensioners, effectively reduces recipient rates, since very high-income pensioners may have their benefit completely reduced. It is projected that 8.0% (or 527,000) of all OAS pensioners in 2020 will be affected by the Recovery Tax. Of this group, 183,000 or 2.8% of all OAS pensioners that year will have their pensions completely reduced. In 2060, those affected by the Recovery Tax are projected to represent 9.9% (1.25 million) of all OAS pensioners, while those fully affected are projected to represent 3.2% (400,000) of pensioners. Section 5 of Appendix D presents more detailed information on the projected impact of the OAS Recovery Tax on the number of OAS basic pension beneficiaries and total amounts payable.

As shown in Table 6 , the number of beneficiaries for the basic pension is expected to increase by 53% over the period 2020 to 2035, growing from 6.6 million in 2020 to 10.1 million by the end of 2035. After 2035, due to the relative stability in the growth of the population aged 65 and over and in the basic pension recipient rates, the number of beneficiaries is expected to continue to increase but at a slower pace to reach 12.7 million by the end of the projection period.

The number of GIS beneficiaries is projected to increase by 55% over the period 2020 to 2035, growing from 2.2 million in 2020 to 3.4 million by 2035. Over that period, the increase in the number of basic pension and GIS beneficiaries is mainly a result of the aging of the population and the retirement of the baby boomers.

It is assumed that, for each cohort of individuals who may become eligible for the GIS or Allowance, the initial retirement income will consist mainly of base and additional CPP and QPP benefits. Both base and additional CPP and QPP benefits increase in line with wage growth prior to retirement and additional benefits further increase as the additional Plans mature. At the same time, it is assumed that the income limits for the GIS and Allowance will have increased in line with inflation prior to retirement. Over the projection period, this combined effect would have the overall effect of reducing the number of individuals who might have otherwise been eligible for the GIS or Allowance benefits. Section 5 of Appendix D provides more detailed information on the projected impact of additional CPP and QPP benefits on the number and total amounts of GIS benefits payable.

The number of Allowance beneficiaries is projected to increase over the period 2020 to 2030, going from 96,000 in 2020 to 102,000 by the end of 2030, with the recipient rates slightly increasing from 3.8% to 4.3% over the same period. After 2030, while the growth in the population aged 60 to 64 stabilizes, the Allowance recipient rate slowly decreases to reach 3.1% (96,000 recipients) by 2060. The expected decrease in the number of Allowance beneficiaries is mainly due to the difference between inflation and wage growth prior to retirement and additional CPP and QPP benefits that are assumed to eventually outweigh any increase in beneficiaries due to the effect of TFSAs.

| Year | Population Age 65+ (thousands) |

Number of Beneficiaries (thousands) | Recipient Rates (percentages) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS | GIS | Allowance | OAS | GIS | Allowance | ||

| 1966 | 1,222 | 1,199 | - | - | 98.1 | - | - |

| 1970 | 1,716 | 1,689 | 816 | - | 98.4 | 47.6 | - |

| 1975 | 1,957 | 1,925 | 1,069 | 74 | 98.4 | 54.6 | 8.2 |

| 1980 | 2,306 | 2,259 | 1,191 | 80 | 98.0 | 51.7 | 8.4 |

| 1985 | 2,648 | 2,595 | 1,290 | 119 | 98.0 | 48.7 | 10.5 |

| 1986 | 2,737 | 2,683 | 1,316 | 139 | 98.0 | 48.1 | 12.2 |

| 1987 | 2,839 | 2,778 | 1,336 | 140 | 97.9 | 47.1 | 12.2 |

| 1988 | 2,929 | 2,862 | 1,342 | 135 | 97.7 | 45.8 | 11.6 |

| 1989 | 3,028 | 2,948 | 1,339 | 128 | 97.4 | 44.2 | 10.9 |

| 1990 | 3,124 | 3,036 | 1,325 | 121 | 97.2 | 42.4 | 10.3 |

| 1991 | 3,212 | 3,127 | 1,309 | 115 | 97.3 | 40.8 | 9.6 |

| 1992 | 3,291 | 3,210 | 1,300 | 110 | 97.5 | 39.5 | 9.2 |

| 1993 | 3,366 | 3,289 | 1,313 | 108 | 97.7 | 39.0 | 8.9 |

| 1994 | 3,434 | 3,367 | 1,340 | 109 | 98.0 | 39.0 | 9.0 |

| 1995 | 3,506 | 3,447 | 1,338 | 108 | 98.3 | 38.2 | 8.9 |

| 1996 | 3,579 | 3,524 | 1,341 | 101 | 98.5 | 37.5 | 8.3 |

| 1997 | 3,654 | 3,594 | 1,364 | 100 | 98.3 | 37.3 | 8.3 |

| 1998 | 3,724 | 3,656 | 1,368 | 97 | 98.2 | 36.7 | 8.0 |

| 1999 | 3,785 | 3,715 | 1,372 | 97 | 98.1 | 36.2 | 7.9 |

| 2000 | 3,851 | 3,781 | 1,363 | 95 | 98.2 | 35.4 | 7.6 |

| 2001 | 3,922 | 3,852 | 1,360 | 93 | 98.2 | 34.7 | 7.2 |

| 2002 | 3,989 | 3,923 | 1,404 | 92 | 98.3 | 35.2 | 6.9 |

| 2003 | 4,061 | 3,999 | 1,450 | 92 | 98.5 | 35.7 | 6.6 |

| 2004 | 4,136 | 4,078 | 1,483 | 93 | 98.6 | 35.8 | 6.3 |

| 2005 | 4,214 | 4,163 | 1,515 | 94 | 98.8 | 35.9 | 6.2 |

| 2006 | 4,319 | 4,261 | 1,546 | 94 | 98.7 | 35.8 | 5.9 |

| 2007 | 4,421 | 4,362 | 1,580 | 94 | 98.7 | 35.7 | 5.5 |

| 2008 | 4,541 | 4,478 | 1,584 | 93 | 98.6 | 34.9 | 5.2 |

| 2009 | 4,669 | 4,603 | 1,595 | 90 | 98.6 | 34.2 | 4.8 |

| 2010 | 4,804 | 4,732 | 1,614 | 92 | 98.5 | 33.6 | 4.6 |

| 2011 | 4,955 | 4,879 | 1,662 | 90 | 98.5 | 33.5 | 4.4 |

| 2012 | 5,155 | 5,076 | 1,701 | 90 | 98.5 | 33.0 | 4.3 |

| 2013 | 5,353 | 5,262 | 1,738 | 84 | 98.3 | 32.5 | 4.0 |

| 2014 | 5,542 | 5,436 | 1,742 | 80 | 98.1 | 31.4 | 3.7 |

| 2015 | 5,722 | 5,597 | 1,798 | 77 | 97.8 | 31.4 | 3.4 |

| 2016 | 5,921 | 5,761 | 1,860 | 73 | 97.3 | 31.4 | 3.2 |

| 2017 | 6,136 | 5,944 | 1,927 | 72 | 96.9 | 31.4 | 3.0 |

| 2018 | 6,358 | 6,154 | 1,985 | 73 | 96.8 | 31.2 | 3.0 |

|

|||||||

| Year | Population Age 65+ (thousands) |

Number of Beneficiaries (thousands) | Recipient Rates (percentages)Table 6 - Footnote 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS | GIS | Allowance | OAS | GIS | Allowance | |||

| 2019 | 6,604 | 6,362 | 2,052 | 71 | 96.3 | 31.1 | 2.8 | |

| 2020 | 6,862 | 6,616 | 2,214 | 96 | 96.4 | 32.3 | 3.8 | |

| 2021 | 7,122 | 6,874 | 2,306 | 97 | 96.5 | 32.4 | 3.7 | |

| 2022 | 7,390 | 7,137 | 2,406 | 97 | 96.6 | 32.6 | 3.7 | |

| 2023 | 7,663 | 7,406 | 2,507 | 98 | 96.6 | 32.7 | 3.7 | |

| 2024 | 7,937 | 7,673 | 2,607 | 99 | 96.7 | 32.9 | 3.7 | |

| 2025 | 8,215 | 7,945 | 2,704 | 100 | 96.7 | 32.9 | 3.7 | |

| 2026 | 8,493 | 8,218 | 2,803 | 101 | 96.8 | 33.0 | 3.8 | |

| 2027 | 8,761 | 8,482 | 2,902 | 102 | 96.8 | 33.1 | 3.9 | |

| 2028 | 9,032 | 8,749 | 3,004 | 103 | 96.9 | 33.3 | 4.1 | |

| 2029 | 9,292 | 9,007 | 3,105 | 103 | 96.9 | 33.4 | 4.2 | |

| 2030 | 9,528 | 9,244 | 3,179 | 102 | 97.0 | 33.4 | 4.3 | |

| 2031 | 9,725 | 9,445 | 3,238 | 101 | 97.1 | 33.3 | 4.2 | |

| 2032 | 9,888 | 9,615 | 3,290 | 99 | 97.2 | 33.3 | 4.2 | |

| 2033 | 10,037 | 9,771 | 3,337 | 98 | 97.3 | 33.2 | 4.1 | |

| 2034 | 10,182 | 9,919 | 3,379 | 96 | 97.4 | 33.2 | 4.1 | |

| 2035 | 10,323 | 10,062 | 3,420 | 94 | 97.5 | 33.1 | 4.0 | |

| 2036 | 10,456 | 10,197 | 3,455 | 93 | 97.5 | 33.0 | 4.0 | |

| 2037 | 10,564 | 10,309 | 3,484 | 92 | 97.6 | 33.0 | 3.9 | |

| 2038 | 10,658 | 10,407 | 3,507 | 91 | 97.6 | 32.9 | 3.8 | |

| 2039 | 10,746 | 10,497 | 3,526 | 90 | 97.7 | 32.8 | 3.7 | |

| 2040 | 10,836 | 10,587 | 3,541 | 89 | 97.7 | 32.7 | 3.6 | |

| 2041 | 10,920 | 10,672 | 3,540 | 87 | 97.7 | 32.4 | 3.5 | |

| 2042 | 11,000 | 10,751 | 3,544 | 87 | 97.7 | 32.2 | 3.4 | |

| 2043 | 11,076 | 10,826 | 3,544 | 87 | 97.7 | 32.0 | 3.3 | |

| 2044 | 11,157 | 10,905 | 3,543 | 87 | 97.7 | 31.8 | 3.2 | |

| 2045 | 11,245 | 10,989 | 3,542 | 87 | 97.7 | 31.5 | 3.2 | |

| 2046 | 11,337 | 11,077 | 3,539 | 87 | 97.7 | 31.2 | 3.2 | |

| 2047 | 11,430 | 11,166 | 3,535 | 88 | 97.7 | 30.9 | 3.2 | |

| 2048 | 11,525 | 11,257 | 3,530 | 88 | 97.7 | 30.6 | 3.1 | |

| 2049 | 11,625 | 11,351 | 3,524 | 89 | 97.7 | 30.3 | 3.1 | |

| 2050 | 11,727 | 11,449 | 3,519 | 90 | 97.6 | 30.0 | 3.1 | |

| 2055 | 12,282 | 11,980 | 3,441 | 92 | 97.5 | 28.0 | 3.0 | |

| 2060 | 12,988 | 12,665 | 3,419 | 96 | 97.5 | 26.3 | 3.1 | |

|

||||||||

4.3. Expenditures and Average Annual Benefits

The historical and projected expenditures and average annual benefits by type are presented in Table 7 and Table 8 . The amounts of OAS basic pension benefits presented in Table 7 and Table 8 do not account for the OAS Recovery Tax in the determination of benefits. The OAS Recovery Tax reduces the OAS basic pension by 15 cents for each dollar of income above a minimum threshold. It is estimated that, in 2020, approximately 8.0% (or 527,000) of all OAS pensioners will be affected by the Recovery Tax, resulting in the repayment of about $2.1 billion or 4.4% of the total amount of basic pensions payable. Section 5 of Appendix D presents more detailed information on the projected impact of the OAS Recovery Tax on the basic pensions payable.

Total basic pension expenditures are projected to increase from $46.3 billion in 2020 to $94.3 billion by 2035 and $195.5 billion by 2060. The projected average annual basic pension of $6,994 in 2020 is equal to about 95% of the projected maximum annual OAS pension for 2020. Since the full impact of the introduction of partial pensions in 1977 (for those with less than 40 years of residence) has been reached , the average annual benefit as a percentage of the maximum is assumed to remain relatively stable at the level of 95% throughout the projection period. The OAS basic pension expenditures and average benefits also account for voluntary deferrals, which became effective 1 July 2013.

The amounts of GIS and Allowance expenditures presented in Table 8 account for additional CPP and QPP benefits that started being paid in 2019. Section 5 of Appendix D presents more detailed information on the projected impact of the additional CPP and QPP on these benefits. For each benefit, total expenditures are the product of the number of beneficiaries and respective average benefit by age, sex, and type and level of benefit.

Total GIS expenditures are projected to increase from $13.7 billion in 2020 to $27.7 billion by 2035 and $45.6 billion by 2060. The projected average annual GIS benefit is $6,361 in 2021 (first year full implementation of new income exemption), which is about 57% of the projected maximum annual GIS single rate for 2021. In the long term, the interaction of TFSAs and additional CPP and QPP benefits results in the average GIS benefit slightly decreasing to about 55% of the maximum GIS single rate by the end of the projection period.

Total Allowance expenditures are projected to increase from $628 million in 2020 to $874 million by 2035 and $1.3 billion by 2060. The projected overall average annual Allowance benefit is $7,376 in 2021 (first year full implementation of new income exemption), which is about 52% of the projected maximum regular annual benefit for 2021. In the long term, the interaction of TFSAs and additional CPP and QPP benefits results in the average Allowance benefit decreasing to about 45% of the maximum Allowance regular rate by the end of the projection period.

Projected total annual OAS program expenditures for all benefits and administrative expenses are $60.8 billion in 2020, rising to $123.4 billion in 2035 and $243.4 billion by 2060. OAS basic pension benefits are projected to be 76% of total expenditures in 2020, and this proportion is expected to increase to 80% by 2060.

| Year | Expenditures ($ million) | Average Annual Benefit ($) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS | GIS | Allowance | Administrative Expenses |

Total | OAS | GIS | Allowance | |

| 1966 | 1,007 | - | - | 5 | 1,012 | 840 | - | - |

| 1970 | 1,611 | 274 | - | 9 | 1,894 | 954 | 336 | - |

| 1975 | 2,883 | 896 | 13 | 10 | 3,802 | 1,498 | 838 | 180 |

| 1980 | 5,147 | 1,772 | 169 | 34 | 7,122 | 2,279 | 1,488 | 2,127 |

| 1985 | 8,696 | 3,278 | 295 | 60 | 12,329 | 3,351 | 2,542 | 2,478 |

| 1986 | 9,346 | 3,419 | 468 | 59 | 13,292 | 3,484 | 2,598 | 3,356 |

| 1987 | 10,070 | 3,577 | 482 | 59 | 14,188 | 3,624 | 2,677 | 3,446 |

| 1988 | 10,774 | 3,725 | 476 | 56 | 15,031 | 3,764 | 2,776 | 3,521 |

| 1989 | 11,579 | 3,851 | 464 | 62 | 15,956 | 3,927 | 2,877 | 3,621 |

| 1990 | 12,484 | 3,954 | 452 | 67 | 16,957 | 4,112 | 2,985 | 3,732 |

| 1991 | 13,545 | 4,102 | 447 | 63 | 18,157 | 4,331 | 3,133 | 3,892 |

| 1992 | 14,292 | 4,227 | 438 | 77 | 19,034 | 4,452 | 3,252 | 3,964 |

| 1993 | 14,872 | 4,393 | 430 | 90 | 19,785 | 4,521 | 3,346 | 3,974 |

| 1994 | 15,403 | 4,587 | 431 | 91 | 20,512 | 4,574 | 3,423 | 3,967 |

| 1995 | 15,832 | 4,601 | 411 | 106 | 20,950 | 4,593 | 3,439 | 3,802 |

| 1996 | 16,433 | 4,636 | 398 | 104 | 21,571 | 4,663 | 3,458 | 3,956 |

| 1997 | 16,944 | 4,710 | 393 | 106 | 22,153 | 4,715 | 3,453 | 3,935 |

| 1998 | 17,470 | 4,810 | 386 | 109 | 22,775 | 4,779 | 3,517 | 3,964 |

| 1999 | 17,903 | 4,894 | 388 | 99 | 23,284 | 4,819 | 3,567 | 3,990 |

| 2000 | 18,669 | 5,019 | 389 | 89 | 24,166 | 4,937 | 3,682 | 4,087 |

| 2001 | 19,508 | 5,160 | 390 | 95 | 25,153 | 5,065 | 3,795 | 4,205 |

| 2002 | 20,318 | 5,417 | 397 | 99 | 26,231 | 5,179 | 3,858 | 4,326 |

| 2003 | 21,217 | 5,710 | 411 | 97 | 27,435 | 5,306 | 3,937 | 4,473 |

| 2004 | 21,923 | 5,954 | 453 | 104 | 28,434 | 5,376 | 4,015 | 4,885 |

| 2005 | 22,701 | 6,334 | 469 | 104 | 29,608 | 5,453 | 4,182 | 4,978 |

| 2006 | 23,737 | 6,800 | 497 | 97 | 31,131 | 5,570 | 4,399 | 5,287 |

| 2007 | 24,711 | 7,346 | 513 | 112 | 32,682 | 5,665 | 4,649 | 5,457 |

| 2008 | 25,925 | 7,425 | 531 | 120 | 34,001 | 5,789 | 4,687 | 5,692 |

| 2009 | 27,149 | 7,708 | 523 | 121 | 35,501 | 5,898 | 4,831 | 5,814 |

| 2010 | 27,984 | 7,807 | 550 | 126 | 36,467 | 5,913 | 4,837 | 5,999 |

| 2011 | 29,528 | 8,434 | 539 | 134 | 38,635 | 6,053 | 5,074 | 5,964 |

| 2012 | 31,423 | 9,029 | 570 | 131 | 41,153 | 6,190 | 5,309 | 6,365 |

| 2013 | 32,893 | 9,349 | 532 | 130 | 42,904 | 6,251 | 5,379 | 6,319 |

| 2014 | 34,506 | 9,538 | 530 | 149 | 44,723 | 6,347 | 5,475 | 6,640 |

| 2015 | 36,167 | 10,240 | 512 | 159 | 47,078 | 6,462 | 5,695 | 6,692 |

| 2016 | 37,780 | 10,657 | 534 | 173 | 49,144 | 6,558 | 5,728 | 7,279 |

| 2017 | 39,693 | 11,528 | 536 | 209 | 51,966 | 6,678 | 5,983 | 7,408 |

| 2018 | 41,784 | 12,174 | 560 | 226 | 54,744 | 6,790 | 6,132 | 7,659 |

|

||||||||

| Year | Expenditures ($ million) | Average Annual Benefit ($)Table 8 - Footnote 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS | GIS | Allowance | Administrative Expenses |

Total | OAS | GIS | Allowance | |

| 2019 | 43,945 | 12,902 | 547 | 230 | 57,624 | 6,907 | 6,287 | 7,706 |

| 2020 | 46,270 | 13,695 | 628 | 242 | 60,835 | 6,994 | 6,187 | 6,526 |

| 2021 | 48,842 | 14,671 | 712 | 257 | 64,482 | 7,106 | 6,361 | 7,376 |

| 2022 | 51,704 | 15,577 | 731 | 272 | 68,284 | 7,244 | 6,474 | 7,532 |

| 2023 | 54,699 | 16,507 | 752 | 288 | 72,246 | 7,386 | 6,585 | 7,680 |

| 2024 | 57,794 | 17,450 | 774 | 304 | 76,322 | 7,532 | 6,692 | 7,818 |

| 2025 | 61,030 | 18,397 | 797 | 321 | 80,545 | 7,681 | 6,804 | 7,941 |

| 2026 | 64,387 | 19,384 | 818 | 338 | 84,927 | 7,835 | 6,915 | 8,064 |

| 2027 | 67,784 | 20,396 | 836 | 356 | 89,372 | 7,991 | 7,028 | 8,191 |

| 2028 | 71,325 | 21,451 | 853 | 375 | 94,004 | 8,152 | 7,142 | 8,313 |

| 2029 | 74,902 | 22,525 | 866 | 393 | 98,686 | 8,316 | 7,255 | 8,440 |

| 2030 | 78,418 | 23,501 | 874 | 411 | 103,204 | 8,484 | 7,392 | 8,557 |

| 2031 | 81,737 | 24,389 | 877 | 428 | 107,431 | 8,654 | 7,532 | 8,706 |

| 2032 | 84,879 | 25,231 | 877 | 444 | 111,431 | 8,828 | 7,669 | 8,841 |

| 2033 | 87,988 | 26,055 | 875 | 460 | 115,378 | 9,005 | 7,809 | 8,979 |

| 2034 | 91,123 | 26,873 | 874 | 475 | 119,345 | 9,187 | 7,952 | 9,117 |

| 2035 | 94,304 | 27,694 | 874 | 491 | 123,363 | 9,372 | 8,099 | 9,255 |

| 2036 | 97,497 | 28,507 | 875 | 508 | 127,387 | 9,562 | 8,250 | 9,394 |

| 2037 | 100,558 | 29,284 | 877 | 523 | 131,242 | 9,754 | 8,405 | 9,542 |

| 2038 | 103,547 | 30,035 | 880 | 538 | 135,000 | 9,950 | 8,564 | 9,694 |

| 2039 | 106,538 | 30,768 | 883 | 553 | 138,742 | 10,149 | 8,727 | 9,848 |

| 2040 | 109,609 | 31,493 | 890 | 568 | 142,560 | 10,353 | 8,894 | 10,002 |

| 2041 | 112,706 | 32,158 | 897 | 583 | 146,344 | 10,561 | 9,084 | 10,292 |

| 2042 | 115,827 | 32,812 | 907 | 598 | 150,144 | 10,774 | 9,260 | 10,453 |

| 2043 | 118,991 | 33,455 | 919 | 613 | 153,978 | 10,991 | 9,439 | 10,618 |

| 2044 | 122,280 | 34,097 | 933 | 629 | 157,939 | 11,214 | 9,623 | 10,782 |

| 2045 | 125,733 | 34,749 | 950 | 646 | 162,078 | 11,441 | 9,812 | 10,944 |

| 2046 | 129,313 | 35,403 | 969 | 663 | 166,348 | 11,674 | 10,004 | 11,108 |

| 2047 | 132,994 | 36,052 | 990 | 680 | 170,716 | 11,911 | 10,199 | 11,274 |

| 2048 | 136,799 | 36,704 | 1,011 | 698 | 175,212 | 12,152 | 10,399 | 11,440 |

| 2049 | 140,746 | 37,367 | 1,035 | 717 | 179,865 | 12,399 | 10,603 | 11,607 |

| 2050 | 144,830 | 38,042 | 1,059 | 736 | 184,667 | 12,650 | 10,810 | 11,779 |

| 2055 | 167,474 | 41,435 | 1,190 | 840 | 210,939 | 13,979 | 12,041 | 12,940 |

| 2060 | 195,531 | 45,604 | 1,329 | 970 | 243,434 | 15,438 | 13,340 | 13,889 |

|

||||||||

4.4. Cost Ratios

Since the program is financed from general revenues on a pay-as-you-go basis, it is useful to express its annual expenditures in relative terms rather than in absolute dollar terms. For this reason, the expenditures are presented as cost ratios using two different measurement bases. The two bases used are total employment earnings and GDP. The details regarding how these measurement bases are projected and adjusted for COVID-19 are provided in section 4 of Appendix D of this report.

Prior to any adjustments for COVID-19, the total employment earnings basis is derived from CPP total employment earnings as projected under the 30th CPP Actuarial Report as at 31 December 2018, adjusted to account for Québec's total employment earnings. The adjustment to account for Québec is determined by using the historical relationship between total employment earnings as published by Statistics Canada and total employment earnings applicable to Canada less Québec for the purpose of the CPP. Adjustments to the job creation rates and unemployment rates were then made over the period 2020 to 2024 to account for the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 11 and Table 12 present the historical and projected annual expenditures as a percentage of total employment earnings.

Prior to any adjustments for COVID-19, the GDP basis is derived from projected total employment earnings using the historical relationship between the two. Table 9 and Table 10 present the historical and projected annual expenditures as a percentage of GDP. Similar adjustments, as done for the total employment earnings basis, were made over the period 2020 to 2024 to account for the COVID-19 pandemic.

The ratio of program expenditures to the GDP is projected to be 2.77% in 2020 compared to 2.50% in 2019. This substantial year-over-year increase is mainly due to the estimated negative impact of COVID-19 on the GDP. The retirement of the baby boomers over the next few decades is projected to increase the expenditures of the program and the ratio is projected to reach a high of 3.1% between 2030 and 2037. Thereafter, although the impacts of TFSAs reduce the amount of income for benefit calculation purposes and tend to increase this ratio over the long term, the growth in additional CPP and QPP benefits and the fact that OAS benefits are indexed to inflation as opposed to wages drive down the cost of the OAS program relative to the GDP over the long term. As a result, annual expenditures are expected to gradually fall to 2.63% of GDP by 2060 which is comparable to the historical levels of the early 1990s.

The projected expenditures shown in Table 10 and Table 12 reflect the eligible ages for program benefits, that is, age 65 and over for the OAS basic pension and GIS, and ages 60 to 64 for the Allowance benefit. The OAS basic pension expenditures also account for voluntary deferrals, which became effective 1 July 2013.

| Year | Gross Domestic Product ($ billion) |

Expenditures as % of Gross Domestic Product Table 9 - Footnote 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS | GIS | Allowance | Administrative Expenses |

Total | ||||

| 1966 | 67 | 1.51 | - | - | 0.01 | 1.52 | ||

| 1970 | 93 | 1.73 | 0.29 | - | 0.01 | 2.03 | ||

| 1975 | 178 | 1.62 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.14 | ||

| 1980 | 323 | 1.59 | 0.55 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 2.21 | ||

| 1985 | 500 | 1.74 | 0.66 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 2.47 | ||

| 1986 | 527 | 1.77 | 0.65 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 2.52 | ||

| 1987 | 574 | 1.75 | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 2.47 | ||

| 1988 | 627 | 1.72 | 0.59 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 2.40 | ||

| 1989 | 672 | 1.72 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 2.38 | ||

| 1990 | 696 | 1.79 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 2.44 | ||

| 1991 | 702 | 1.93 | 0.58 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 2.59 | ||

| 1992 | 718 | 1.99 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 2.65 | ||

| 1993 | 747 | 1.99 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 2.65 | ||

| 1994 | 792 | 1.94 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 2.59 | ||

| 1995 | 832 | 1.90 | 0.55 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 2.52 | ||

| 1996 | 860 | 1.91 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 2.51 | ||

| 1997 | 907 | 1.87 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.44 | ||

| 1998 | 941 | 1.86 | 0.51 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.42 | ||

| 1999 | 1,008 | 1.78 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.31 | ||

| 2000 | 1,106 | 1.69 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.18 | ||

| 2001 | 1,145 | 1.70 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.20 | ||

| 2002 | 1,194 | 1.70 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.20 | ||

| 2003 | 1,255 | 1.69 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.19 | ||

| 2004 | 1,336 | 1.64 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.13 | ||

| 2005 | 1,422 | 1.60 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.08 | ||

| 2006 | 1,497 | 1.59 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.08 | ||

| 2007 | 1,578 | 1.57 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.07 | ||

| 2008 | 1,657 | 1.56 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.05 | ||

| 2009 | 1,571 | 1.73 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.26 | ||

| 2010 | 1,666 | 1.68 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.19 | ||

| 2011 | 1,774 | 1.66 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.18 | ||

| 2012 | 1,827 | 1.72 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.25 | ||

| 2013 | 1,902 | 1.73 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.26 | ||

| 2014 | 1,995 | 1.73 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.24 | ||

| 2015 | 1,990 | 1.82 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.37 | ||

| 2016 | 2,026 | 1.87 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.43 | ||

| 2017 | 2,141 | 1.85 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.43 | ||

| 2018 | 2,224 | 1.88 | 0.55 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.46 | ||

|

||||||||

| Year | Gross Domestic Product ($ billion) |

Expenditures as % of Gross Domestic ProductTable 10 - Footnote 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS | GIS | Allowance | Administrative Expenses |

Total | ||||

| 2019 | 2,304 | 1.91 | 0.56 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.50 | ||

| 2020 | 2,193 | 2.11 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.77 | ||

| 2021 | 2,357 | 2.07 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.74 | ||

| 2022 | 2,486 | 2.08 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.75 | ||

| 2023 | 2,587 | 2.11 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.79 | ||

| 2024 | 2,700 | 2.14 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.83 | ||

| 2025 | 2,794 | 2.18 | 0.66 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.88 | ||

| 2026 | 2,890 | 2.23 | 0.67 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.94 | ||

| 2027 | 2,990 | 2.27 | 0.68 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.99 | ||

| 2028 | 3,094 | 2.31 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.04 | ||

| 2029 | 3,201 | 2.34 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.08 | ||

| 2030 | 3,312 | 2.37 | 0.71 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.12 | ||

| 2031 | 3,429 | 2.38 | 0.71 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.13 | ||

| 2032 | 3,552 | 2.39 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.14 | ||

| 2033 | 3,679 | 2.39 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.14 | ||

| 2034 | 3,812 | 2.39 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.13 | ||

| 2035 | 3,950 | 2.39 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.12 | ||

| 2036 | 4,087 | 2.39 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.12 | ||

| 2037 | 4,231 | 2.38 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.10 | ||

| 2038 | 4,382 | 2.36 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.08 | ||

| 2039 | 4,539 | 2.35 | 0.68 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.06 | ||

| 2040 | 4,700 | 2.33 | 0.67 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.03 | ||

| 2041 | 4,869 | 2.32 | 0.66 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.01 | ||

| 2042 | 5,044 | 2.30 | 0.65 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.98 | ||

| 2043 | 5,227 | 2.28 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.95 | ||

| 2044 | 5,416 | 2.26 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.92 | ||

| 2045 | 5,610 | 2.24 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.89 | ||

| 2046 | 5,809 | 2.23 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.86 | ||

| 2047 | 6,016 | 2.21 | 0.60 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.84 | ||

| 2048 | 6,228 | 2.20 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.81 | ||

| 2049 | 6,445 | 2.18 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.79 | ||

| 2050 | 6,667 | 2.17 | 0.57 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.77 | ||

| 2055 | 7,870 | 2.13 | 0.53 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.68 | ||

| 2060 | 9,255 | 2.11 | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.63 | ||

|

||||||||

| Year | Total Employment Earnings ($ billion) |

Expenditures as % of Total Employment EarningsTable 11 - Footnote 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS | GIS | Allowance | Administrative Expenses |

Total | ||||

| 1966 | 31 | 3.21 | - | - | 0.02 | 3.22 | ||

| 1970 | 46 | 3.53 | 0.60 | - | 0.02 | 4.15 | ||

| 1975 | 89 | 3.24 | 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 4.27 | ||

| 1980 | 156 | 3.29 | 1.13 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 4.55 | ||

| 1985 | 232 | 3.75 | 1.41 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 5.32 | ||

| 1986 | 247 | 3.78 | 1.38 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 5.37 | ||

| 1987 | 269 | 3.75 | 1.33 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 5.28 | ||

| 1988 | 295 | 3.65 | 1.26 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 5.10 | ||

| 1989 | 319 | 3.63 | 1.21 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 5.01 | ||

| 1990 | 333 | 3.74 | 1.19 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 5.09 | ||

| 1991 | 339 | 4.00 | 1.21 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 5.36 | ||

| 1992 | 343 | 4.17 | 1.23 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 5.55 | ||

| 1993 | 347 | 4.28 | 1.27 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 5.70 | ||

| 1994 | 356 | 4.33 | 1.29 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 5.76 | ||

| 1995 | 366 | 4.32 | 1.26 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 5.72 | ||

| 1996 | 376 | 4.37 | 1.23 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 5.74 | ||

| 1997 | 398 | 4.26 | 1.18 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 5.57 | ||

| 1998 | 421 | 4.15 | 1.14 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 5.41 | ||

| 1999 | 445 | 4.02 | 1.10 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 5.23 | ||

| 2000 | 486 | 3.84 | 1.03 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 4.98 | ||

| 2001 | 504 | 3.87 | 1.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 4.99 | ||

| 2002 | 521 | 3.90 | 1.04 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 5.04 | ||

| 2003 | 541 | 3.92 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 5.07 | ||

| 2004 | 571 | 3.84 | 1.04 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 4.98 | ||

| 2005 | 605 | 3.75 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 4.90 | ||

| 2006 | 645 | 3.68 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 4.83 | ||

| 2007 | 685 | 3.61 | 1.07 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 4.77 | ||

| 2008 | 716 | 3.62 | 1.04 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 4.75 | ||

| 2009 | 705 | 3.85 | 1.09 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 5.03 | ||

| 2010 | 728 | 3.85 | 1.07 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 5.01 | ||

| 2011 | 767 | 3.85 | 1.10 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 5.04 | ||

| 2012 | 800 | 3.93 | 1.13 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 5.15 | ||

| 2013 | 829 | 3.97 | 1.13 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 5.18 | ||

| 2014 | 861 | 4.01 | 1.11 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 5.19 | ||

| 2015 | 884 | 4.09 | 1.16 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 5.32 | ||

| 2016 | 880 | 4.29 | 1.21 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 5.58 | ||

| 2017 | 922 | 4.30 | 1.25 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 5.64 | ||

| 2018 | 966 | 4.33 | 1.26 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 5.67 | ||

|

||||||||

| Year | Total Employment Earnings ($ billion) |

Expenditures as % of Total Employment Earnings Table 12 - Footnote 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS | GIS | Allowance | Administrative Expenses |

Total | ||||

| 2019 | 1,000 | 4.39 | 1.29 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 5.76 | ||

| 2020 | 976 | 4.74 | 1.40 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 6.24 | ||

| 2021 | 1,037 | 4.71 | 1.41 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 6.22 | ||

| 2022 | 1,085 | 4.77 | 1.44 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 6.29 | ||

| 2023 | 1,128 | 4.85 | 1.46 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 6.41 | ||

| 2024 | 1,173 | 4.93 | 1.49 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 6.51 | ||

| 2025 | 1,213 | 5.03 | 1.52 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 6.64 | ||

| 2026 | 1,255 | 5.13 | 1.54 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 6.77 | ||

| 2027 | 1,298 | 5.22 | 1.57 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 6.88 | ||

| 2028 | 1,343 | 5.31 | 1.60 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 7.00 | ||

| 2029 | 1,390 | 5.39 | 1.62 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 7.10 | ||

| 2030 | 1,438 | 5.45 | 1.63 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 7.17 | ||

| 2031 | 1,489 | 5.49 | 1.64 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 7.21 | ||

| 2032 | 1,542 | 5.50 | 1.64 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 7.22 | ||

| 2033 | 1,598 | 5.51 | 1.63 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 7.22 | ||

| 2034 | 1,655 | 5.51 | 1.62 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 7.21 | ||

| 2035 | 1,715 | 5.50 | 1.61 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 7.19 | ||

| 2036 | 1,775 | 5.49 | 1.61 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 7.18 | ||

| 2037 | 1,837 | 5.47 | 1.59 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 7.14 | ||

| 2038 | 1,903 | 5.44 | 1.58 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 7.09 | ||

| 2039 | 1,971 | 5.41 | 1.56 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 7.04 | ||

| 2040 | 2,041 | 5.37 | 1.54 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 6.98 | ||

| 2041 | 2,114 | 5.33 | 1.52 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 6.92 | ||

| 2042 | 2,191 | 5.29 | 1.50 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 6.85 | ||

| 2043 | 2,270 | 5.24 | 1.47 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 6.78 | ||

| 2044 | 2,352 | 5.20 | 1.45 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 6.72 | ||

| 2045 | 2,436 | 5.16 | 1.43 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 6.65 | ||

| 2046 | 2,523 | 5.13 | 1.40 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 6.59 | ||

| 2047 | 2,612 | 5.09 | 1.38 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 6.53 | ||

| 2048 | 2,704 | 5.06 | 1.36 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 6.48 | ||